In 1995, I was given a diagnosis named borderline personality disorder (BPD). I was 13 years old. Prior to this diagnosis, I experienced depression and felt a range of emotions strongly. These feelings were complicated by my parents divorce in 1994 and difficulties at school. It wasn’t until 1995 when I began self-harming frequently that I sought help. The problem is, there was no help in 1995 for BPD, let alone, being a male with such a diagnosis.

Stigma associated with BPD includes negative stereotypes portrayed by media, some police, some general health care workers and the general public who misunderstand what BPD is.

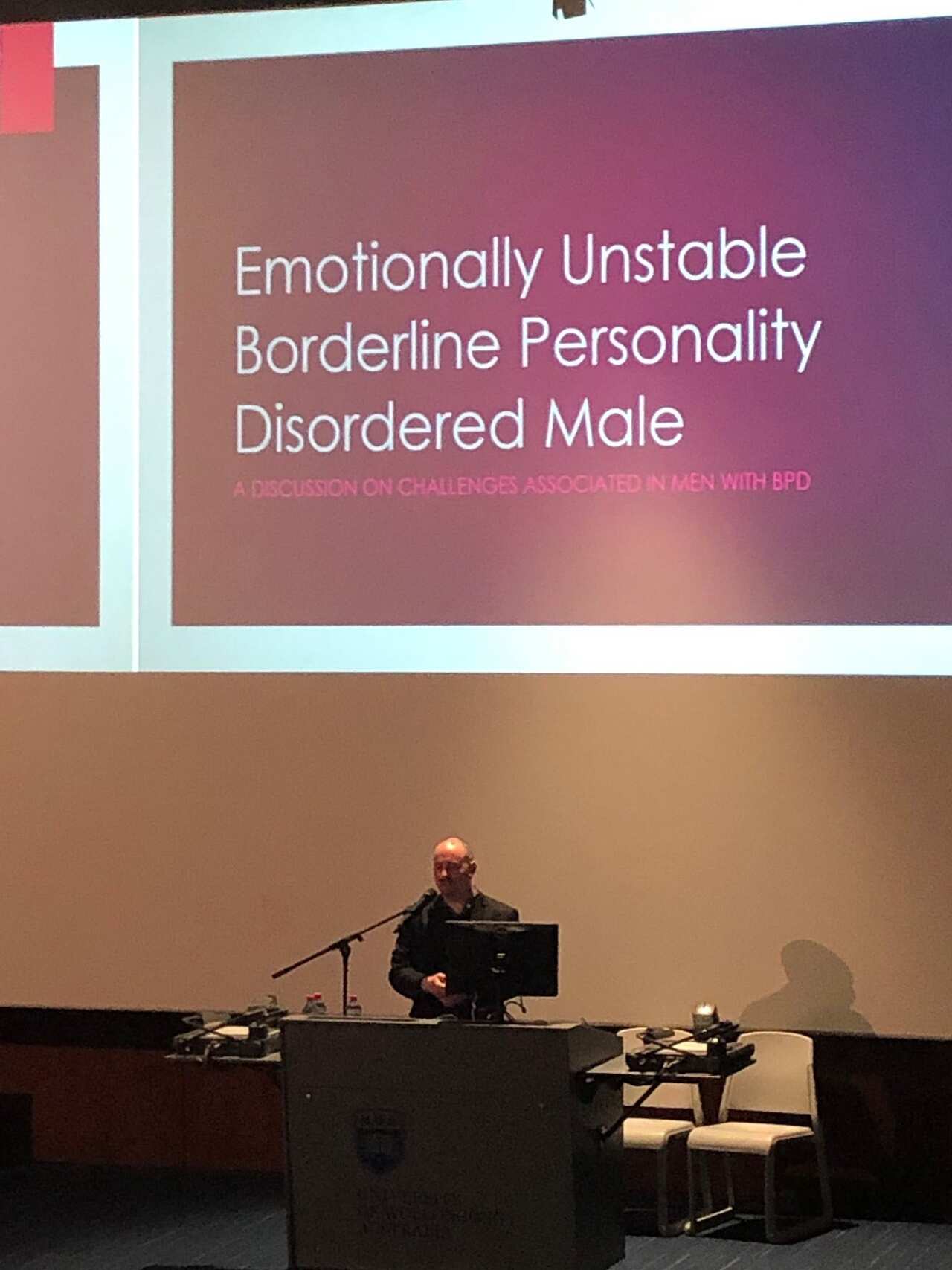

BPD involves a fear of abandonment, emotional dysregulation, self-harm (although not everyone with BPD self-harms), a term called ‘splitting’ (ranging from falling head over heels for someone to completely devaluing them) and difficulties with perception in others. BPD is relatively prevalent in Australia with four per cent of the population affected at some point in their life. BPD has a high suicide rate, one in 10 will suicide. While BPD is diagnosed more frequently in women at a ratio of 3:1, this does not mean more women necessarily live with the disorder. There is a diagnostic bias that see men misdiagnosed or worse: men don’t come forward to seek treatment at all. There is no cure for BPD however treatments have advanced, so a person may function well enough to manage in life.

During adolescence, I called helplines quite frequently. The telephone conversations I had with counsellors often produced a variety of mixed results. Sometimes calling a service would create more problems because police would turn up at my mother’s house at 2am, waking her and other family members up, for the police or ambulance to take me to hospital because I’d said to a counsellor that I felt like dying. Other times, helplines were helpful: I would come away feeling empowered to deal with my issues, however these were rare and were dependent on the level of understanding from a counsellor. Other opinions from phone counsellors were unhelpful, often discussions that BPD is a load of nonsense and a ‘wastebasket’ diagnosis. I felt calling helplines was an abuse of trust at times; decisions to call police or emergency services resulted in situations escalating. Some people look at helplines as ‘well if it saves a life’ however that is a simplistic attitude and not very helpful in establishing trust. Disclaimers often cited by helplines as justification for calling police, paradoxically prevent people from calling in the first place.

BPD has seen an increase in the offering of treatment since I was a teenager, however there are long waitlists in years, not months. The public are misguided on the extent of mental health help available when the reality is, people with BPD will struggle to trust telehealth services. What is frustrating is that both federal and state governments have been shown the economic benefits in investing in treatment options by those in the mental health field. An initial investment would reduce costly presentations to hospital, yet little is done in providing more access to treatment. I feel an irritating rhetoric by the government is an attitude towards using existing resources ‘more efficiently’ is counterproductive. Stigma associated with BPD includes negative stereotypes portrayed by media, some police, some general health care workers and the general public who misunderstand what BPD is. Once I was threatened with legal action for calling out a ‘life coach’ on their malignant attitude and publication on BPD. BPD is not manipulative or attention-seeking behaviour. The risk of suicide is very real but treatment can help.

I currently work for the South Australian Government and have for the last eight years. I am a final year law student and advocate on mental health matters. I co-run a social media group for people with BPD.

Changes I would like to see include an increase to the amount of sessions a person with BPD may receive under the Better Access to Medicare Scheme. I feel like the Health Minister, Greg Hunt MP, is not responsive to more sessions for those suffering from BPD, yet ironically raised sessions for eating disorders. I’d like to see the media stop using BPD as a catchphrase in association with sensationalising certain social problems that have no context. Further, I would like the media to consult with associations like Sane Australia and the BPD Foundation Australia, so issues are presented in a fair, informed, unbiased and objective manner. I feel the media have a critical role in portraying mental illness appropriately and refraining from reinforcing negative stereotypes associated with all mental illness, not just BPD. Lastly, I’d like to see both federal and state Governments working collaboratively on mental health, instead of employing a football attitude towards accountability. Oddly, the federal government discuss zero-target initiatives associated with suicide yet, areas like BPD are the most neglected in mental health but have some of the highest rates of suicide within Australia.

I hope more is done in this area, sooner rather than later to prevent suicide.

Helplines:

If you, or someone you know, is struggling with mental health issues you can contact:

Lifeline via their website or on 13 11 14,

Sane Australia via their website or on 1800 18 7263,

Beyond Blue via their website or on 1300 22 4636 or

Kids Helpline via their website or on 1800 55 1800.

Aaron Fornarino works and lives in South Australia and completing a law degree. Aaron lives with borderline personality disorder.

Insight is Australia's leading forum for debate and powerful first-person stories offering a unique perspective on the way we live. Read more about Insight

Have a story or comment? Contact Us