With ageing parents living longer and children not leaving home, what's it like to be stuck in the middle? Watch Insight episode Sandwich Generation on SBS On Demand.

Julie-Anne Dietz's parents both have dementia. While her father is living in aged care, her 82-year-old mother doesn't want to enlist any aged care services — meaning she primarily relies on the support of Julie-Anne and her sisters.

"The expectations that my mother has of me and my sisters is basically what she modelled to us, when she looked after her own mother."

However, knowing she has a finite amount of time with her mother, Julie-Anne says she'd "really like to be a daughter rather than a carer".

Julie-Anne is a member of the 'sandwich generation': people who are caring for their parents, while also supporting their own children.

While people have always cared for older people and the young, the 59-year-old says it's harder for her generation compared to her mother's.

"Her life at 60, is very different to my life at 60," Julie-Anne says. "She was retired ... I'm still working full-time."

Julie-Anne has two daughters in their early 20s with her husband Grant. Millie has moved out while Annabelle still lives at home.

Grant believes they rely on them as parents too much. Julie-Anne says she is more "hands-on" with her adult daughters than her mother was with her.

"This is my first turn at being a daughter … and being a mother," Julie-Anne says. "So, this is my first rodeo at trying to balance those things together."

A responsibility to fulfil?

While caring for both parents and children at the same time can be overwhelming for some, it's an expected cultural norm for others.

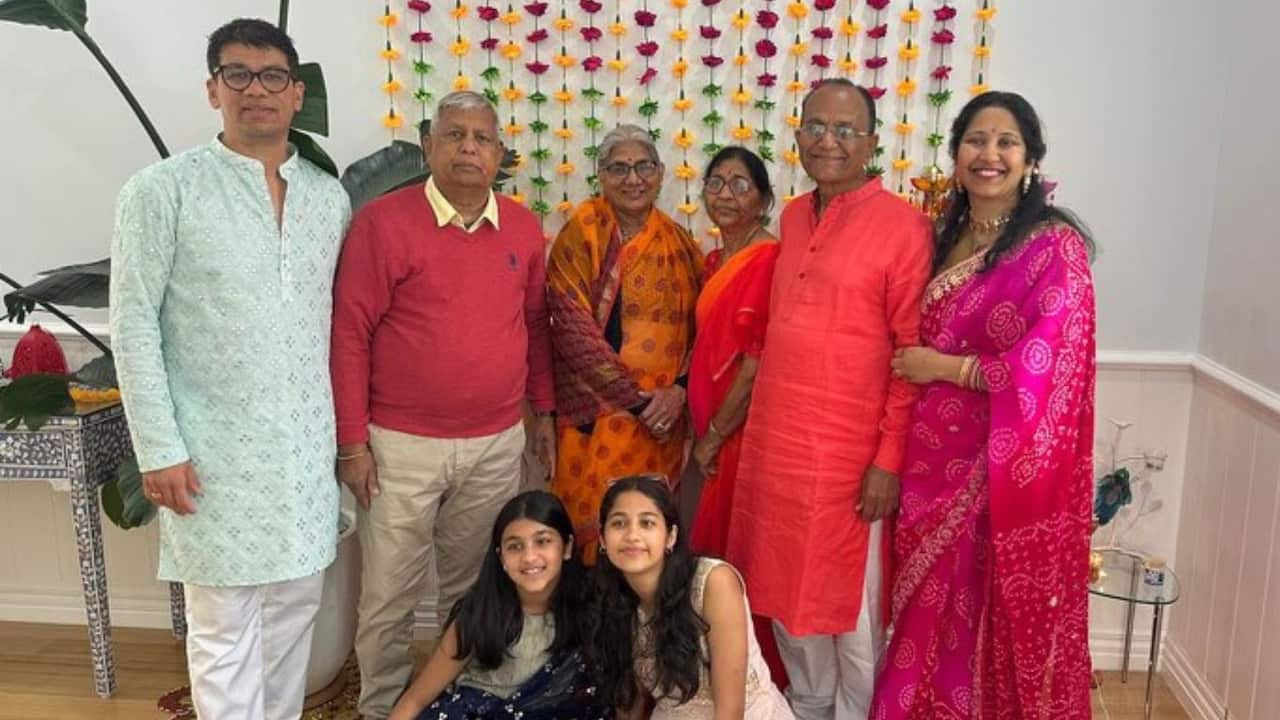

Sid Kawar and his wife Irina moved Sid's parents from India to Melbourne in 2021, to live with them and their two teenage daughters in a purposely built, five-bedroom home.

Sid notes that because parents look after their children until their early 20s in India, it is the responsibility of the child — usually the son — to look after their parents for a similar amount of time.

"We don't prefer to send our parents to aged care," he says. "It is looked down on by the society".

Irina agrees: "We won't be at peace with ourselves if we do that to our parents".

"What if they [had done] the same to us when we were kids?"

GenX faces a unique situation

Demographer Mark McCrindle says in 2025 "we've got a larger sandwich generation than ever".

The median age of registered deaths in Australia is 79.6 years for males and 84.6 years for females, according to a 2023 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report, which is higher than we've seen in the past.

He notes that older generations are not only living longer but are also increasingly living independently, "and that can really only happen with the support of their children".

McCrindle says that with the rising costs of living and housing, the average age young adult leaves home is closer to the mid-20s age bracket. This means that many offspring are financially dependent on their parents for longer than previous generations.

"So, what you end up with, is parents still with dependent children well into their 20s," the demographer says, "right at the time that their own parents are getting elderly and are needing support".

This leaves people typically in their 40s and 50s, like Julie-Anne — some even in their 30s — squeezed in the middle.

Managing expectations

Psychologist Melissa Levi, who specialises in ageing and caregiving, says being 'sandwiched' is an overwhelming experience because people must juggle so many responsibilities.

"[We want] to be the best caregiver to our mum or dad, be a present parent, nurture a marriage, keep down a job, be a friend."

The psychologist says people who are sandwiched can feel resentment and experience burnout if they do not put boundaries in place. Boundaries that help to prevent conflict by managing expectations.

"It can feel counterintuitive for the child essentially to set the boundary with the parent," Levi says.

"You're setting your family up for success if you've got really clear, loving boundaries."

For Phyllis Foundis, setting boundaries with her 94-year-old mother, who lives independently, was an essential but difficult thing to do.

"I realised that if there were no boundaries then everyone would suffer," Phyllis said of being sandwiched between caring for her mother and two teenage sons.

"It doesn't mean that I … love her any less, but I need to be very strong and present, not only for my sons and my mother, but for myself."

The future of the 'sandwich generation'

For Sid and Irina, living with and caring for Sid's parents is something they feel enriches their lives.

In their multigenerational household, their teenage daughters learn Hindi from their grandparents and enjoy their grandmother's home-cooked meals.

Living together also means Sid can financially help his parents and help with translating during his father's medical appointments.

"If we can look after our kids," Sid says, "why can't we look after our parents"?

Conversely, as a key provider of care to her mother, Julie-Anne feels her time spent "as mother-daughter as opposed to mother-carer" is diminishing.

She hopes that by setting herself up well enough for the future, this is a role her daughters won't have to step into when she reaches older age.

"I just really look forward to sharing a life with them," Julie-Anne says.

"And that they are my daughters, and I am their mother".

And for more stories on sex, relationships, health, wealth, grief and more, head to Insightful — an SBS podcast series hosted by Kumi Taguchi. Follow us on the SBS Audio App, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Insight is Australia's leading forum for debate and powerful first-person stories offering a unique perspective on the way we live. Read more about Insight

Have a story or comment? Contact Us