Ms Tongs will always remember the day she sat across from her abuser, looked him in the eye, and asked him, ‘Why?’

“I needed to hear it from his voice,” she tells Insight.

Despite a trial, a conviction and a six-year jail sentence, Ms Tongs felt the court process didn’t give her the answers she was looking for.

“[Court is] a very, very hard system to go through as a victim,” she says.

“It's long, there's lots of delays…you feel like you're on trial and that’s difficult because the perpetrator doesn't even have to take the stand.

“I went there to get justice and you don't really come out of it necessarily feeling you get that.”

After a parole hearing, Nicki’s offender began to admit to the abuse he’d inflicted on her as a child and she realised the potential for a conversation she’d never had.

Restorative justice is a facilitated meeting – or other form of communication – between a victim, offender and support people. It’s a voluntary process and requires an offender’s admission of wrongdoing.

It took two tries before Ms Tongs felt comfortable with her abuser entering the meeting room where she waited.

“He was like this monster to me and so it was very difficult, but unlike the court system, this process is more survivor-focused,” she says.

“It's about my needs and wants and making me feel safe.”

Could it work in Australia?

New Zealand has used restorative justice for more than two decades. In Australia, the practice is typically used in juvenile cases and has only been applied to adults in limited forms.

In 2017, the ACT extended the application of restorative justice to adult victims and offenders of sexual assault. The state’s Restorative Justice Unit plans to take referrals in such cases from July this year.

[videocard video="1170327107630"]

“The process would be very strong on accountability from the offender and not putting a victim through anything that would be distressing or too uncomfortable,” says Restorative Justice Unit manager Amanda Lutz.

The program only takes referrals from within the traditional justice system, from bodies including police, child protection services, the courts, corrective services and the DPP.

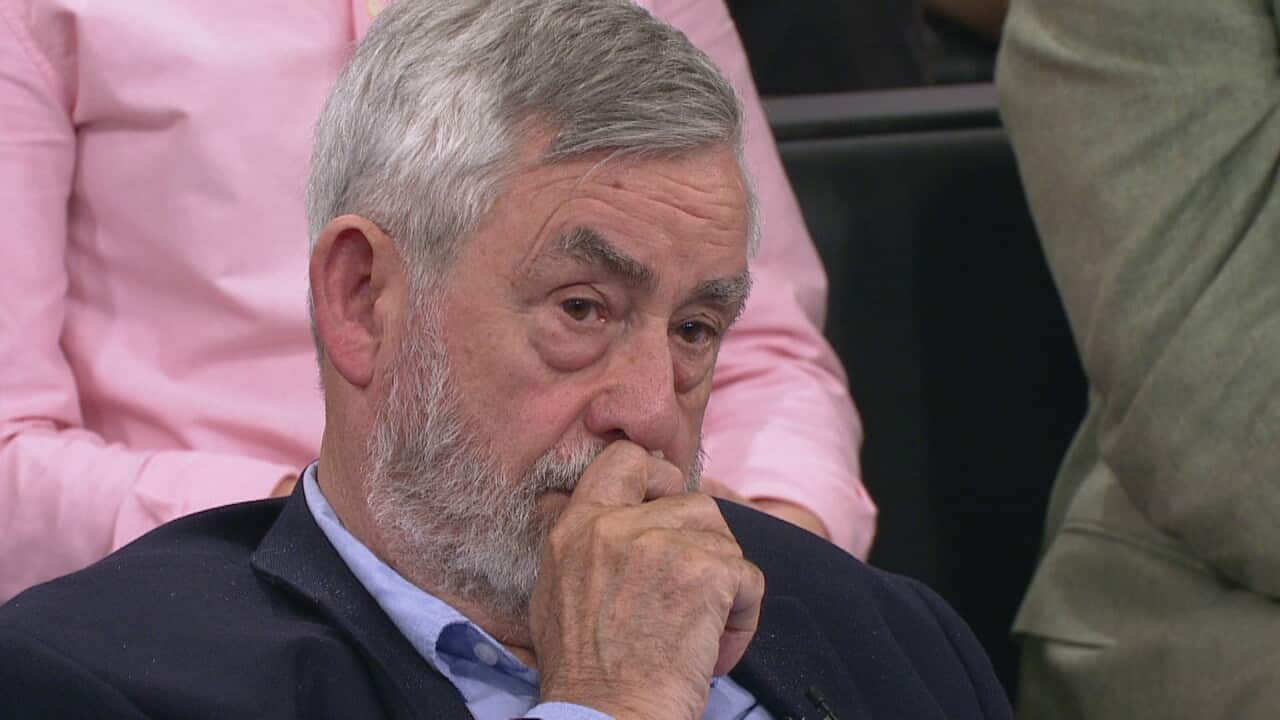

It’s a change that Rob Hulls, head of the RMIT Centre for Innovative Justice, wants to see more widely adopted.

“Victims have a whole range of needs that will never be met through the current trial process, so we have to give victims options other than the adversarial process,” he says.

Mr Hulls hopes to see restorative justice implemented as an appendage to the courts, so victims have the option to go ahead with it either in addition to, or instead of, trial.

But some feel the approach risks confining discussion of sexual assault to behind closed doors.

Liz Bishop, who is part of a team from the Michael Kirby Institute for Public Health and Human Rights at Monash University, acknowledged the opposition to this - while recognising that if done correctly it could work.

"One of the feminist arguments against using restorative justice in this setting is there's a chance for re-traumatisation and there's a chance for the offender to perpetrate other and different [harms] against the person who they've already traumatised," she tells ABC.

For Ms Tongs, the conversation with her abuser helped her to heal.

“I spent a lot of time blaming myself and for me that process allowed me to shift that blame onto him where that actually belongs,” she says.

“I walked away with a real level of strength.”

Support services

National

Sexual Assault & Domestic Violence National Help Line

1800 Respect (1800 737 732)

A full list of state-based services can be found here.

Insight is Australia's leading forum for debate and powerful first-person stories offering a unique perspective on the way we live. Read more about Insight

Have a story or comment? Contact Us