Insight explores how different people overcome loneliness. Overcoming Loneliness, Tuesday March 18 at 8:30pm on SBS and SBS On Demand.

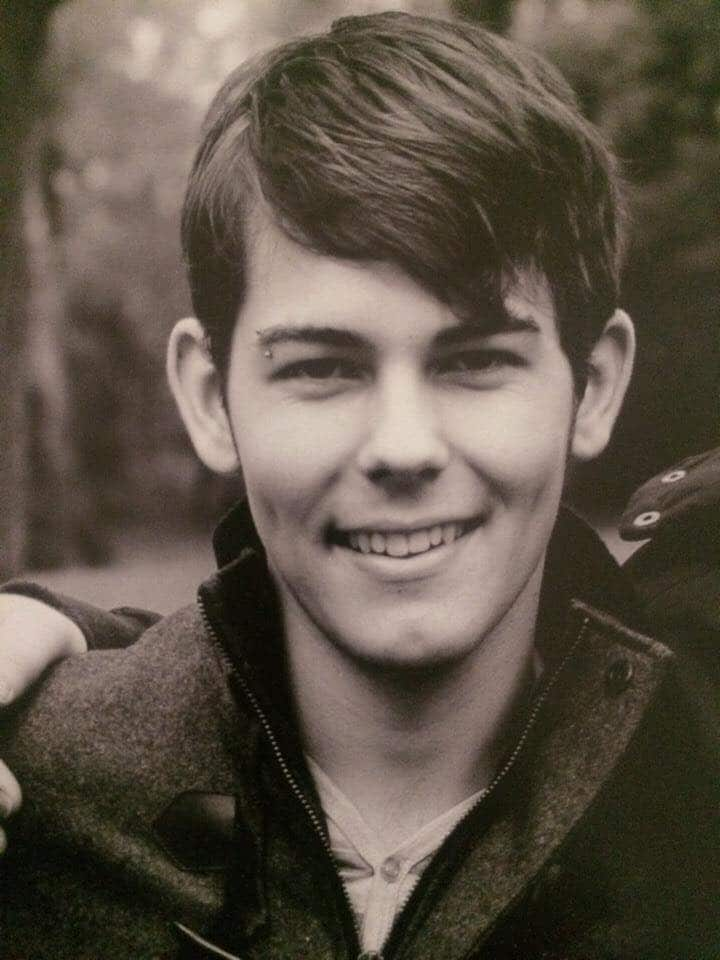

As long as Kaine Anderson can remember, he has never really had friends.

Even in high school, when there were constantly people around, he still felt lonely.

“I didn’t feel I fit in. There was no one group I could go to. There was not one person that I can say I connected with during high school,” he says.

Many school-leavers will feel lost when they graduate but Kaine’s disconnection meant he eventually isolated himself from the outside world for over two years.

“I didn’t have any connections with anyone, didn’t have anywhere else to go. I was living in my parent’s garage... and all I did was paint and draw and watch movies”.

While he admits he shut himself off, pretty soon his loneliness lead to more problematic mental health issues.

“When you’re alone, the whole universe is crammed in your brain. It’s swirling around and you develop anxiety … it spins and spins until the voice of a person you love smacks you out of it.”

Loneliness is defined as a subjective feeling of isolation meaning it’s less about the number of people around you but, instead, about how you perceive the strength of those connections.

Clinical psychologist and research fellow, Dr Michelle Lim, explains that as thirst tells us to drink water, loneliness tells us we need to connect with people. “It’s innate. It’s a signal for us to connect and reach out.”

The Australian Loneliness Report recently revealed loneliness in Australia is on the rise with one in four Australians feeling lonely at least three days a week.

The report also shows lonely people are more likely to be depressed or anxious. But experts are now questioning… do they always go hand in hand?

"You don’t have to have a mental health diagnosis to be lonely," Dr Lim says.

In fact, longitudinal studies show loneliness is more likely to lead to future mental ill-health than the reverse.

One study showed that if a person with a history of depression joins one social group, they reduce their risk of relapse by 24 per cent; if they joined three groups, that risk is reduced by 63 per cent.

As Dr Lim puts it, “loneliness predicts depression; depression does not predict loneliness.”

For Kaine, that was certainly the case.

Now 28, and living with his long-term partner, Kaine was recently diagnosed with depression and prescribed antidepressants. He feels confident he may not be depressed if he had more friends in his life.

“When I’m going through a bad time - family drama or relationship issues - I have no one to bounce that off of … I have to internalise it and keep it to my chest,” he explains.

He says loneliness is still something he deals with all the time. “It’s a shadow you can’t get rid of. It follows you all day every day. Sometimes it’s smaller and sometimes it’s bigger. Sometimes it swallows you whole and it gets really dark.”

But Kaine says when he feels that way now, instead of staying inside, he tries to get out of the house.

“I love going to a café and sitting there, knitting and drawing. You have to get out… when you come back home, you will feel a bit different, you have gotten out of a pattern”.

Dr Lim says there is still a lot we don’t know about treating loneliness and the first step is to focus on accumulating “good science and good data”.

But she is hopeful, “[this research] suggests that if you address loneliness, it is likely to alleviate depression."

Insight is Australia's leading forum for debate and powerful first-person stories offering a unique perspective on the way we live. Read more about Insight

Have a story or comment? Contact Us