Listen to Australian and world news, and follow trending topics with SBS News Podcasts.

TRANSCRIPT

"With the parties signatures today the agreement immediately enters into force, thank you very much. Congratulations."

After three decades of violence, top diplomats from Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo have signed a peace agreement in Washington D-C.

It comes after an escalation earlier this year when the M23, a primarily ethnic Tutsi rebel force linked to Rwanda, moved across the mineral-rich east of the DRC, seizing vast territory and conducting summary executions.

Despite doubts the deal will bring a quick end to conflict, the Qatari - US facilitated agreement seen as a major turning point.

Rwandan Foreign Minister Olivier Nduhungirehe says it will still be a difficult path to peace.

"We must acknowledge that there is a great deal of uncertainty in our region and beyond because many previous agreements have not been implemented. And there is no doubt that the road ahead will not be easy. But with the continued support of the United States and other partners, we believe that a turning point has been reached."

The agreement has provisions on territorial integrity, prohibition of hostilities and the disengagement, disarmament and conditional integration of non-state armed groups.

With veiled optimism, Congo's Foreign Minister Thérèse Kayikwamba Wagner says there is still plenty of work to be done.

"This moment has been long in coming. It will not erase the pain, but it can begin to restore what conflict has robbed many women, men, and children of, safety, dignity, and a sense of future. For the Great Lakes region, it offers a rare chance to turn the page, not just with words, but with real change on the ground. Some wounds will heal, but they will never fully disappear. They may grow over, but the skin will forever remain thin and frail. And deep down, the flesh will still remember."

With roots in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, the conflict has displaced seven million people in the Congo and has killed millions in the last three decades.

It has been described by the United Nations as one of the most protracted, complex and serious humanitarian crises on Earth.

While both countries pledged to pull back support for armed rebel groups, the most prominent armed group in the conflict, M-23, has suggested the deal is not binding to them.

Speaking to Al Jazeera, national security law and foreign policy expert Johanna LeBlanc says the key armed groups should be involved in talks at some stage.

"I'm optimistic. I do think that there are some areas in the deal that causes some of us to pause, because we still don't know who is supposed to deliver, what, when and how, right? And also the main fighters, the M23 as well as FDLR, they were not at the table. They were not consulted. So I think that in order to be truly successful, it would require consultation with them, maybe not at the at the initial stage, it would have been better perhaps at some point, Rwanda, DRC or the United States, will bring those two groups to the table to also get them to sign an agreement."

The DRC government has long alleged that M23, consisting mostly of ethnic Tutsis, receives military support from Rwanda.

These claims are backed by Washington.

While Rwanda denies directly supporting the M23, they demand an end to another armed group, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda.

The agreement calls for the 'neutralisation' of the FDLR, which was established by ethnic Hutus linked to the massacres of Tutsis in the 1994 Rwanda genocide.

The DRC hopes the U-S will provide it with security support to fight the rebels and possibly get them to withdraw from key cities.

Thérèse Kayikwamba Wagner says it is vital that the U-S commits to this deal.

"Stay committed, stay on board. We need the United States to make sure that this agreement holds and that you hold us accountable. And the third point is, if you stay on board, I think there are so many perspectives that we can transform our partnerships through and that can usher in an era of prosperity, of growth, and of shared bilateral relationships that go well beyond the challenges that we've shared together and that can at least or finally focus on the potential and of the wealth that we can share."

In the eastern DRC city of Bukavu, residents are expressing cautious hope for peace, with many citing urgent security concerns that disrupt daily life.

Local residents like Don Bwami say peace will bring great joy to the region.

"We hope that the coming days will bring us a peaceful situation and that the weapons will fall silent. When weapons fall silent, we will also live a normal situation and this will be appreciated by everyone. Not just here in the East, even our friends in the West will be very happy with this situation. So peace is nothing but peace."

In the Rwandan capital of Kigali, residents say they too are optimistic about the deal, expressing hope for a revival in cross border trade.

Locals like Celestin Nshimiyimana say the easing of tensions will benefit everyone.

"There are indeed benefits to signing these agreements, both in terms of business and cross-border relations. For example, many Rwandans used to work in Congo, but due to the current insecurity, they no longer go there. However, if these agreements are implemented and things run smoothly, both sides will be able to operate freely, which will be beneficial for both parties."

While the deal is being touted as an important step towards peace, it also sits at the heart of US President Donald Trump's push to gain access to critical minerals.

The DRC is the world’s top cobalt supplier, and Chinese companies are the biggest miners and buyers.

The US Department of Commerce estimates the mostly untapped minerals are estimated to be worth as much as $24 trillion USD.

Rwanda also has been accused of exploiting eastern D-R-C's minerals, used in smartphones, advanced fighter jets and much more, Rwanda denies this.

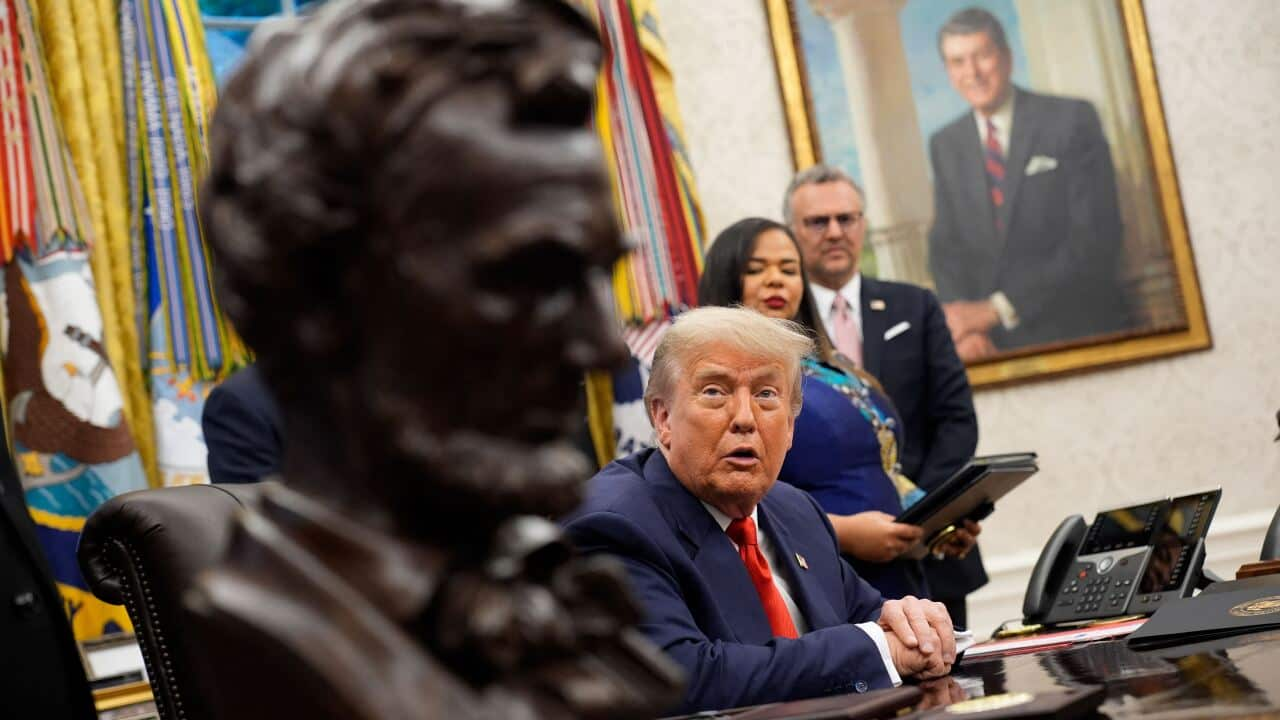

Ahead of the signing, Donald Trump told reporters he doesn't know too much about the region, but still takes credit for the deal.

"So, I'm a little out of my league in that one because I didn't know too much about it. I knew one thing, they were going at it for many years, and with machetes. It is one of the worst, one of worst wars that anyone's ever seen. And I just happened to have somebody that was able to get it settled. I mean, just a brilliant person who is very comfortable in that part of the world. It's a very dangerous part of world. They said, are you uncomfortable there? People are being killed, school children are being raided and killed. And I don't even want to say how, but as viciously as I've ever heard. Are you uncomfortable? No, that's the part of that world that I know. Very uncomfortable. Was able to get them together and sell it. And not only that, we're getting for the United States a lot of the mineral rights from the Congo as part of it. So honored to be here."

While the deal has already drawn widespread praise, it has not been universal.

Groups like Physicians for Human Rights, which has worked in the DRC, say the agreement has major omissions, including accountability for rights violations.

Other critics say the deal is about access to natural resources.

Johanna LeBlanc says the deal is just as much about money as it is about peace.

"I think it was a forward thinking proposal. Because you're talking about providing the United States access to more than $24 trillion of the world's most critical minerals. You're talking about cobalt, lithium, right, which are all essential for a green and tech economies here in the United States. So this deal is just [as much] about peace as it is about economic possibilities. And let me tell you this where there are minerals, there are influence in Washington wants to be at the centre of it."