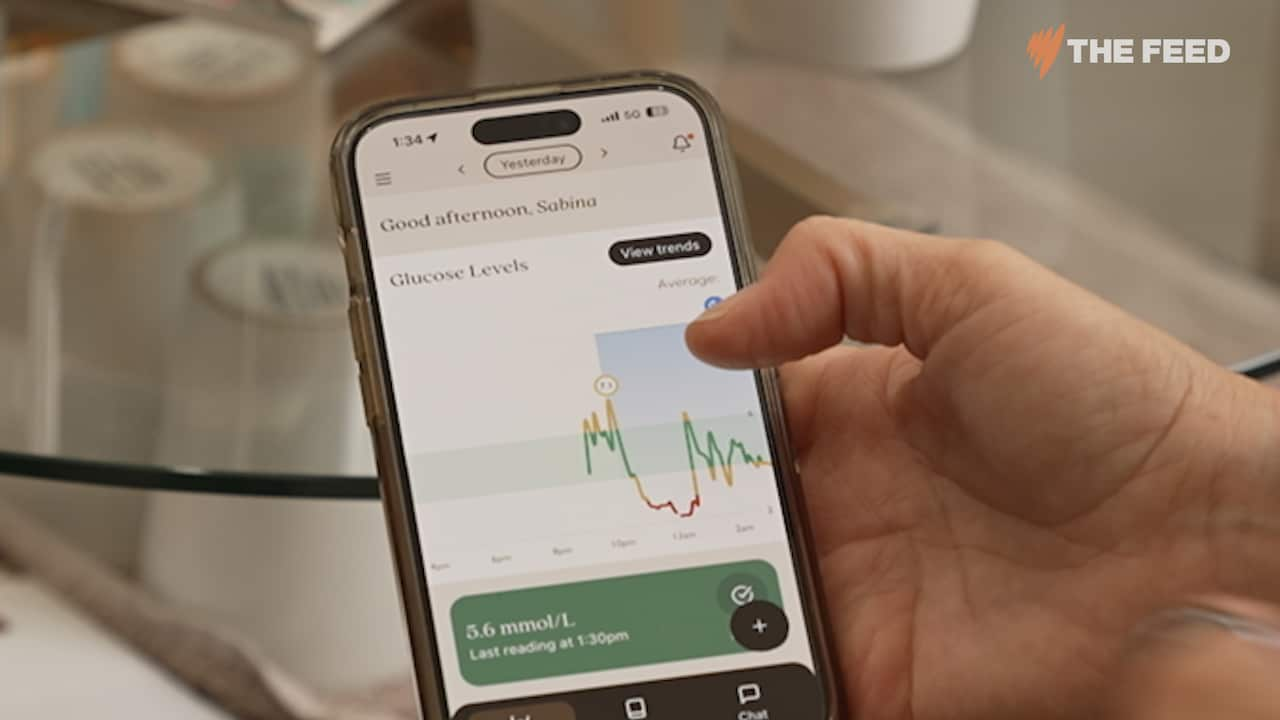

As Sabina Ziokowski checks her blood glucose levels on an app, she notices a spike in the chart.

"I had my dinner last night — pizza. And you'll see it sort of spiking up there," Sabina, 52, tells The Feed as she scrolls through her data.

She's monitoring her blood glucose (or sugar) levels in real time, using a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) which is placed at the back of her arm.

"After that initial spike, it kind of crashed down and I think that's what woke me up in the middle of the night."

Sabina checks her app around five times a day, monitoring how her body reacts to food, sleep, caffeine and stress through blood glucose levels.

She's used three CGMs over the course of two years. Each sensor cost her just under $300 and lasted between 10 and 14 days.

Sabina sees CGMs as part of her "health journey".

"There's things that you can optimise [with health] and you can see, and then there's things that you can't see," she says.

CGMs are wearable devices inserted into the skin with a filament. They were first designed for people who live with diabetes, allowing them to manage the condition and prevent their blood sugar rising or dropping to levels that can cause medical emergencies. But now they're being marketed to people without diabetes as a wellness tool.

"Once I found out that somebody who was non-diabetic could get one here and use it, I jumped on it as soon as I could," Sabina says.

Vively is a company that sells CGMs and markets them to non-diabetics — and put The Feed in touch with Sabina.

Online, social media influencers claim CGMs are helping manage their energy, fitness and health, but some experts — like Dr Karen Spielman, a Sydney GP and research associate at InsideOut Institute, Australia's research, education, and policy reform institute for eating disorders — fear they could lead to misguided decision-making around food.

"It's very, very dangerous to be using the information to minimise blood sugars in a healthy person. That really worries me," Spielman told The Feed.

Interpreting the data

Some researchers are concerned CGM use for people without diabetes may cause unnecessary anxiety around eating, as people misinterpret normal glucose spikes.

Sabina said she quit snacking after watching her glucose levels on her CGM app.

"Each time you snack, you can be giving yourself a spike in blood sugar and then insulin," she said.

"It can create a bit of a yo-yo effect."

She believed snacking spiked her blood sugar levels, which she felt translated into mood swings.

"I was finding that when I was snacking, I'd also be getting 'hangry' — my blood sugar would come up and then drop down again."

Sabina also used the data to cut down to a strict three meals a day regime and also made changes to her diet.

"I used to like oatmeal, but for me, it really spiked my blood sugar."

Now she sticks to protein-heavy breakfasts, like eggs or yoghurt.

For most people, snacking helps maintain blood sugars in a healthy range, according to Spielman.

"We need to be eating three to four hourly to keep our blood sugars in a healthy range for optimal muscle function, brain function, heart function," Spielman says.

"You really don't want to be skating on the low side — that's very, very dangerous."

Without oversight from a doctor or health practitioner, people without diabetes run the risk of misinterpreting data, according to Amy-Lee Bowler, a sports dietitian from the University of the Sunshine Coast.

"I think the risk that we run is that a lot of non-athletic populations don't 100 per cent properly understand what's happening with that data and why glucose fluctuates throughout the day," Bowler told The Feed.

"We should never really expect our glucose to run on a flat line."

She's also concerned about an overload of data.

"You're provided with your glucose every 15 minutes over a 24-hour period for about two weeks. That's a lot of data."

"I definitely think there is a real risk of us becoming overly fixated on the data and listening less to our bodies."

Sabina acknowledges there are spikes the CGM shows on her app that she can't fully explain.

"There are unusual spikes and things that scratch my head sometimes … but if I'm not sure, that gives me something else to read up on and find out about," she says.

Feeding anxiety around eating

Spielman is also concerned that CGMs and other biohacking devices could fuel anxieties around eating, including "orthorexia", which is an obsession with eating healthy food.

"When I first heard of CGMs, it kind of freaked me out to think that it's possible for my patients who are already overly anxious about the impacts of food on their bodies to have this kind of information."

She believes people using CGMs may be more inclined to restrict food unnecessarily based on the data they're seeing.

"This kind of information may fall into the hands of people who may have excessive worries or may overinterpret or may do unhealthy things with the information," she says.

"Sugar is one aspect, but healthy balanced eating and lifestyle and moving one's body in a way that makes one feel happy and good mental health and connection, social connection and access to services are all probably just as if not more important than a simple blood sugar reading."

Unclear benefits

While researchers note there is a trend of the devices being used by people without diabetes, there is limited evidence of the benefit of this population using CGMs, according to a report published by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health website in the US in January.

Michael Fang, a diabetes and wearable technologies researcher, noted that "no major clinical trials have attempted to demonstrate" that wearing a CGM could lower a person's risk of developing chronic diseases and help with weight management — but said some smaller tests have shown short-term benefits for people without diabetes.

Vively's co-founder Dr Michelle Woolhouse said it's normal for people to be confused about the data but said CGMs may be useful in identifying undiagnosed metabolic issues for some users.

"About 7.5 per cent of people in Australia have pre-diabetes … It doesn't come with any symptoms and it often goes undiagnosed," Woolhouse told The Feed.

But Spielman says having a health professional to help the user understand the data is integral.

"We love having lots of information — and being able to make more informed decisions about health is a good thing — so long as it's done cautiously with reputable sources of information and under the guidance of your trusted GP."

Changing stigma

Caitlin Rogers lives with type 1 diabetes and told The Feed CGMs are crucial in managing her condition.

"It's probably one of the most important pieces of technology I use in my life and is more of a lifesaving device than just a piece of 'tech'," Rogers said.

More than 80 per cent of people with diabetes report feeling "blamed or shamed" for their condition, according to Diabetes Australia. The organisation is helping promote a global pledge aimed at eliminating diabetes stigma, and Rogers hopes general use of CGMs could help to lessen this stigma.

"I would like to see the mainstream use of CGMs used to help open up a healthy conversation about this technology for people with diabetes and the full scope of benefits it offers for people living with this condition and not just becoming a trend or fad."

This article provides general information only and should not be considered medical advice. It is not intended to replace the advice provided by your doctor or medical / health professional.

Through award winning storytelling, The Feed continues to break new ground with its compelling mix of current affairs, comedy, profiles and investigations. See Different. Know Better. Laugh Harder. Read more about The Feed

Have a story or comment? Contact Us