Meet the Tiwi man using the power of bush medicine to revive his community

Wurankuwu Traditional Owner Ron Poantumilui is hoping modern science met with cultural practices will create the jobs and resources needed to revive his community.

Published

Walking through the vast bushland of Wurankuwu on Bathurst Island - one of the Tiwi Islands just north of Darwin - Ron Poantumilui is proud to call this Country home.

"This is my backyard and the ocean out there, that is my front yard," he told NITV.

For generations, his people, the Wurankuwu clan, have harvested their Country for food and traditional bush medicine.

One of those is a species is the Corymbia Nesophila, a bloodwood tree endemic to northern Australia.

Its thick, blood-red sap, crystalises like a ruby once dry and is known for its healing properties.

Wurankuwu Elders say it can be processed into a paste to treat skin conditions.

"When someone has the scabies, when you put the cream on the scabies it will clean it after two days and then it will go away," Mr Poantumiliui said.

It's one of more than a dozen known medicinal plants found on the Tiwi Islands islands.

Knowledge of how they're used has been passed down for generations, with Tiwi Elders documenting it in a book.

"All those knowledge is part of our Tiwi foundation, it was given to us by our ancestors," Tiwi Elder Molly Munkara told NITV.

With job creation and economic development in mind, elders on the Tiwi Islands partnered with Menzies School of Health Research and industry giant Integria Healthcare to explore the commercial potential for some of those species.

Integria's Head of Research, Dr Elizabeth Steels says a decade of work has gone into testing the traditional knowledge.

She says the results have been exciting, with three plants expected to reach global markets in the next two years.

"Potentially you go down the path of clinical trials ... we then create an industry for the Tiwi where they can create their own medicinal medicine industry, and that's not been done in Australia," Dr Steels said.

Medicinal plant use in Australia is currently dominated by material sourced overseas.

"We process probably over 200 herbs from other parts of the world, but none from Australia," Dr Steels said.

Botanist Dr Greg Leach has been instrumental in work to develop medicinal plants in the north.

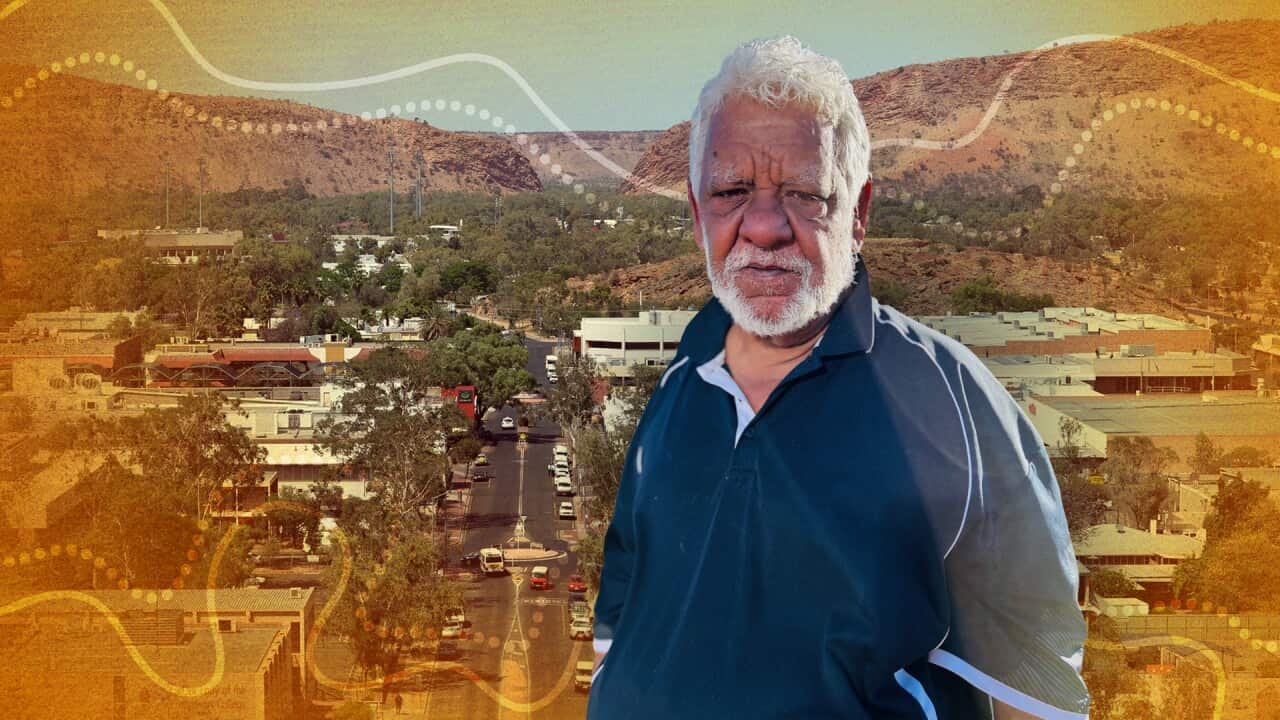

The Honorary Fellow at Menzies School of Health Research started documenting plant species from Alice Springs to the Top End 30 years ago.

Working with Aboriginal communities, he documented more than a hundred medicinal plants as part of that collection.

"A lot of people challenge this sort of work about the Indigenous knowledge, but those books and other publications have effectively put that knowledge in the public domain," Dr Leach said.

He's excited about the next step.

"We are currently in the throws of actually trying to get assesment for approval by the Therapeutic Goods Administration, which of course is the Australian Federal approvals body," Dr Leach said.

TGA approval is critical in getting some of these plant species to market.

That will require looking at how the Tiwi people have documented the medicinal properties of plants and their use.

"That actually requires a lot of dollars and quite a lot of hard data ... supporting what your claim is about therapeutic use."

For the people of Wurankuwu, proving the traditional science could be transformative for their community.

"This project it means a lot to me and my people... at the moment there is no project for my people to work," Mr Poantumilui said.

In Wurankuwu, Ron sits at an empty primary school.

Currently, the 50 or so people that live here have relocated to Wurruminyanga, a community on the island's southeast, while housing infrastructure is updated.

It's a welcome investment in one of the most remote communities in the country, but more is needed.

Wurankuwu is cut off by road for months during the monsoonal wet season, impacting job security in an area starved of employment.

Coupled with other farming trials planned for Wurankuwu, elders believe this project could create half a dozen jobs for this community.

"I want to see my people come back and living back home," Ron Poantamilui said.