Warning: this article contains details that may be distressing to some readers.

On the 26 January 1838, a public holiday was declared to mark the 50th anniversary of the colony.

In Sydney, crowds gathered along the harbour, their celebration marked with an ‘anniversary’ regatta and fireworks.

It was described as a 'day for everyone.'

But while the colony celebrated, another story was unfolding.

More than 600 kilometres north, Aboriginal men, women and children were being hunted down and slaughtered.

That year, Foundation Day - the day that would later become Australia Day - was marked by events that could not have been more black and white.

The expanding frontier, and Aboriginal resistance

At the centre of this story is a man named James Winniett Nunn.

Nunn was a career army officer and veteran of the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815).

He’d arrived in the colony of NSW in July 1837 with the 80th Regiment of Foot - an infantry regiment of the British Army - and by September was seconded to command the NSW Mounted Police.

Nunn took charge of operations to protect squatters on the colony's frontier from Traditional Custodians defending their ancestral lands.

By 1837, the expanding colonial frontier had reached Gamilaroi Country (Gamilaroi is also spelt/pronounced Kamilaroi, Gamilaraay or Gomeroi), vast land in northeastern New South Wales and southern Queensland, that stretched from the Great Dividing Range in the east to areas near Walgett in the west.

Aboriginal nations were dispossessed of their lands, which were taken for farming and grazing without consent.

In the colony of NSW, ‘squatters’ were graziers who occupied vast areas of Crown land for grazing beyond the officially sanctioned ‘Nineteen Counties.’

These counties marked the colony’s recognised ‘limits of location.’ Those who settled and ran livestock on land outside this jurisdiction were classified as squatters, despite their occupation often becoming permanent and highly profitable.

Despite the uncertainty of land tenure, squatters ran large numbers of sheep and cattle beyond the boundaries. From 1836, they could legally do so, paying £10 per year for the right.

As the colony expanded beyond these boundaries, Aboriginal nations were dispossessed of their lands, which were taken for farming and grazing without consent. Land loss destroyed access to food sources, sacred and significant sites and cultural practices tied to Country.

This was Country owned and occupied by Aboriginal people for tens of thousands of years.

Within the first 50 years of the Colony, violence and frontier conflict was widespread as Aboriginal people fought back against the taking and settlement of their lands.

Lethal clashes increased.

An Australian massacre

In April 1836 on the Gwydir River, a squatter named Thomas Simpson Hall, who had already established runs at Barraba, decided to move his cattle further north to new pastures.

Hall encountered strong resistance from the local Gamilaroi, who attacked his party, killing one stockman, rushing the cattle and wounding Hall.

Forced to retreat, Hall retaliated by mounting a posse comprised of mounted police, local squatters and farmhands.

The posse returned to the area in July 1836 and over two weeks hunted down and shot a large number of Aboriginal people, killing an estimated 80.

On 18 December 1837, it was reported that Gamilaroi warriors had again attacked and killed stockmen on properties in the Namoi and Big River district beyond the limits of settlement in the Namoi River district. (The 'Big River' was the early colonial name for the Gwydir River.)

The killings were the latest of five separate incidents in which stockmen on the new pastoral runs on the Gwydir River were attacked or killed.

These incidents, along with other skirmishes, were used to apply pressure on the government to take a stand against Aboriginal attacks.

On 19 December 1837, the then NSW acting governor, Lieutenant-Colonel Kenneth Snodgrass, sent for Major Nunn to come to Government House.

He ordered Nunn to go out to the Liverpool Plains and deal with the Gamilaroi people’s resistance to British occupation.

Nunn was instructed by Snodgrass to:

"act according to your judgement and use the utmost exertion to suppress these outrages. There are a thousand blacks there, and if they are not stopped, we may have them presently within the boundaries [of the nineteen counties].’ "

Nunn had also been issued with specific instructions that empowered him to ‘repress as far as possible the aggressions complained of.’ As a military man, Nunn understood exactly what this meant.

Some ten days later, Nunn departed with a heavily armed detachment, consisting of one Subaltern, two Sergeants and twenty troopers - the party would be close to 40 strong by the time it arrived at the Namoi boosted by additional troopers and local stockmen.

They had assembled at Jerrys Plains – a base for the Mounted Police which today is a village in the Hunter Valley, about 33 kilometres west of Singleton.

Nunn and his party headed straight to the Namoi River, widely looking for the those believed responsible for the 'outrages' – the term used for attacks and killing of white squatters and their livestock.

Nunns’ interactions with the Gamilaroi from this moment onwards would later be the subject of an official inquiry, conducted in Sydney in April and May 1839 (some 15 months after the event) by a police magistrate and two Justices of the Peace.

On January 4 or 5 at the lower Namoi (near present day town of Manilla), Nunn and his mounted party were led to a large group of Gamilaroi camped at the river - a number he later estimated to be ‘about a hundred persons.’

With the assistance of an interpreter, Nunn says he ‘communicated to the tribe that they were charged with murder, spearing cattle and all manner of outrages.’ He demanded that the actual perpetrators of these acts of violence should be ‘delivered up to me’ - to be taken into custody.

Nunn and his party took into custody 15 men - with two men being pointed as those responsible for the killing of a stockmen on a nearby property some 18 months previous and set the 100 strong group free.

About two hours before sunset, Nunn returned to his former camp with the 15 prisoners, the two men charged with murder were secured by handcuffs and placed in the charge of two sentries.

Slipping their handcuffs after night fall, the two men attempted to escape. One succeeded, but the other was shot in back by a sentry.

As the dead man was believed to be the one responsible for the murder of a servant on a property some 9 months earlier, Nunn says the other 13 prisoners were subsequently liberated, all except one, who he retained with as a guide.

The killing of the servant had actually happened on the Gwydir River, completely different country from the mob that Nunn had just captured and released.

Nunn and the party then headed Northwest to towards stations on the Gwydir River pursing a group of Gamilaroi along the Namoi for three weeks which he believed were responsible for the escalation outages on nearby properties. He had orders to capture those responsible.

'War of extermination'

On the morning of 26 January 1838, near the Gwydir River, his party found a large group of Gamilaroi - men, women and children – camped at a waterhole now known as Snodgrass Lagoon (named by explorer Thomas Mitchell in 1832 after the man who had sent Nunn on the hunt for the “aggressive blacks”).

The Lagoon is the lower waters of Waterloo Creek near modern Bellata.

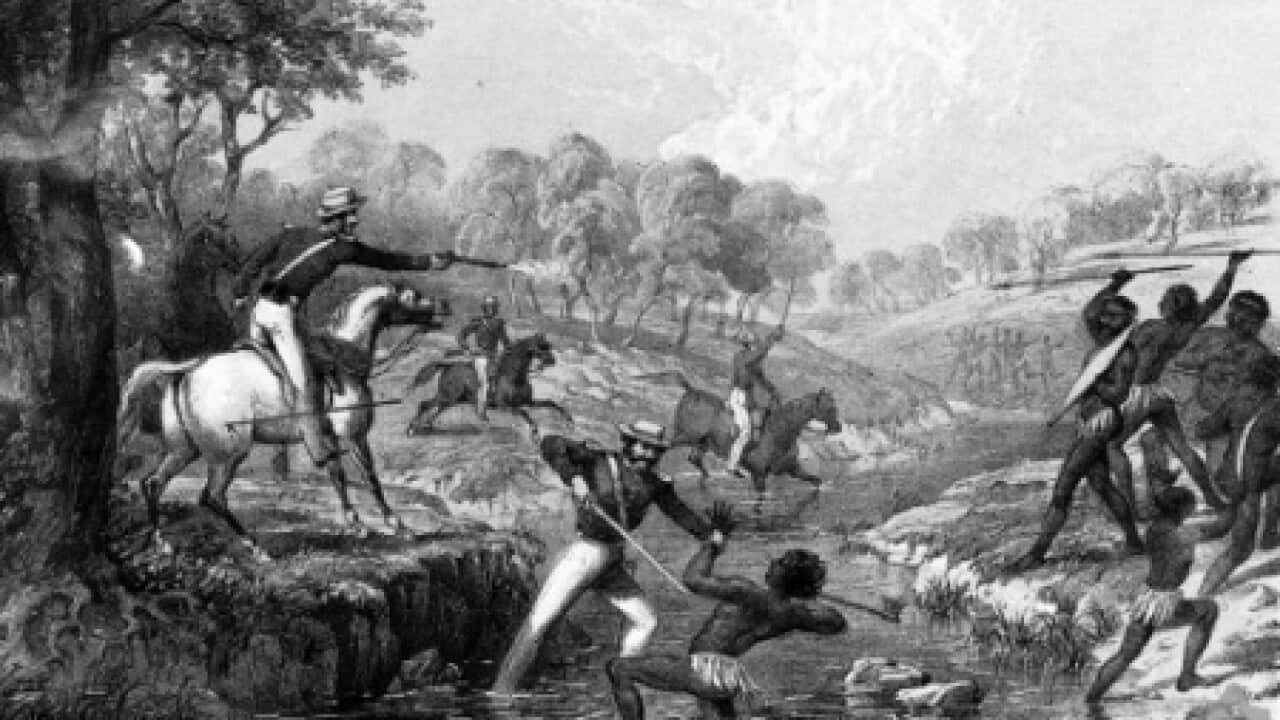

Nunn ordered his troops to surround the group and advance.

With second-in-command Lieutenant George Cobban at the front and Major Nunn at the rear (some 50 metres away), the party advanced at pace through the scrub with swords drawn.

As they charged through the group, swords drawn and opening fire, Corporal Patrick Hannan was wounded in the calf with a spear.

In the ensuring panic, and in retaliation, each ‘man acted for himself.’ The firing then became general and indiscriminate, and a number of Gamilaroi were killed.

At the later inquiry, Sergeant John Lee noted that in hunting for the Gamilaroi that “there was no remission in the pursuit from the time the firing began until it ceased altogether.”

No Gamilaroi were apprehended. None were questioned in relation to the killing of pastoralists or livestock. No Gamilaroi were taken into custody for the killings.

Only Death.

The number of deaths from this interaction is contentious. Nunn says it was only a handful.

Nunn’s two sergeants were later questioned at the inquiry in Sydney. One, who rode at the back of the group, said four or five Aboriginal people were killed. The other, who rode at the front, listed the death toll as 40 or 50.

On their return journey through the foothills, the posse engaged in a typical frontier style ‘mopping up’ operation, hunting down and killing any Aboriginal person they encountered.

Nunn had fulfilled his orders with murderous dispatch, and he received a hero’s welcome in the towns on his return route.

The English missionary Reverend Lancelot Threlkeld, who worked by Awabakal in the Hunter Region, suggested between 200-300 people were killed in this campaign.

Vigilante-settlers continued Nunn’s campaign, riding the country, shooting Aboriginal people they could find, in what Muswellbrook Magistrate Edward Denny Day would come to call a ‘war of extermination’ on the Gwydir.

The belated official inquiry held 15 months after the murders was carried out by the colonial government, but there were no prosecutions, and the matter was eventually dropped.

The Waterloo Creek massacre is one of 150 mass killings recorded in a mapping project by the University of Newcastle.

These are not isolated events.

They are part of the foundation story of this nation - stories that are not taught.

Back in Sydney on January 26, 1838 - at midday, 50 guns fire from Dawes Point. The Royal Standard is raised. By evening, fireworks light the sky. Dinner parties fill homes across the town. Glasses were raised to toast to Queen Victoria, the Governor, and the success of the Colony.

The day is described as “a day for everyone”.

These are not competing histories. They are the same history.

Both are the story of us. The story of this nation.

And yet, for many Australians, January 26 still tells the story of only some of us.