Speaking to David Williams, he suddenly stops, to draw attention to a bird call.

"Hear that? That's a crow. That was Pemulwuy's totem."

The two men are similar: Pemulwuy has been called the first Aboriginal resistance fighter; and Williams likewise fought for his people, during the Vietnam War.

And much like Pemulwuy, who ferociously defended his lands and people against the encroaching British invasion, it was due to a reluctant sense of duty that Williams went to battle.

"I didn't sign up to fight in any war," he told NITV News.

"I signed up to protect Australia, because the government of the day was telling us how bad some people were around the world."

Australian War Memorial releases list of First Nations fighters

Mr Williams, 75, is one of 29 members of his extended family to give their services in war, from the Australian Light Horse (a skilled formation of mounted infantry in World War I), to his own time in the Royal Australian Navy, and up until the present day.

Now, for the first time, his time in the Vietnam war, as well as those of up to 250 other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, has been recognised by the Australian War Memorial.

Systemic racism, and the desire to downplay and eradicate the efforts of Indigenous soldiers, is partly to blame for the late recognition, but so too was the recruitment practices of the time.

"I signed up as an Australian, and I had an ID card... it said 'Australian', 'Complexion: dark'," said the Bundjalung man.

The historically hidden wartime contributions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are slowly being brought to light; stories like Mr Williams are being recognised and celebrated for the first time.

While he and other Vietnam veterans may find some solace in the acknowledgment of their sacrifice, such moves come too late for the First Nations fighters who served in older conflicts. Mr Williams says he himself struggled to learn about them when he was growing up.

"It's a start," he said.

'It gave us skills'

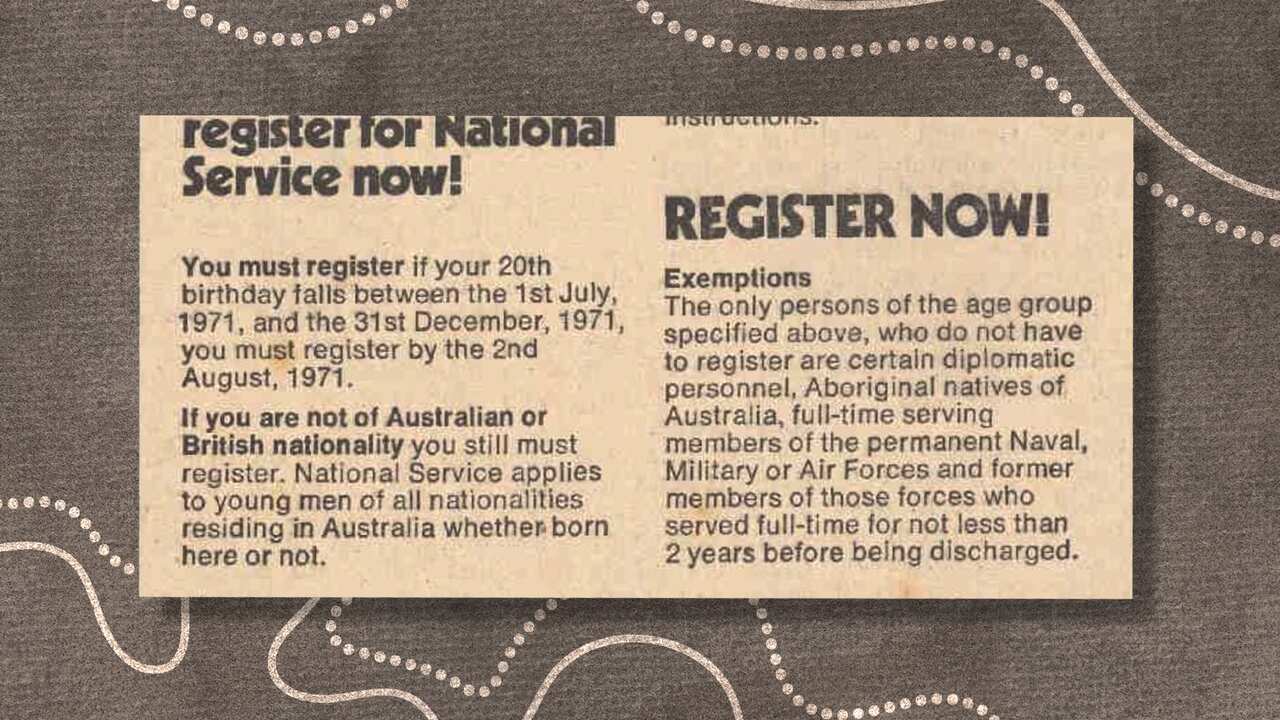

Little did he know at the time that no Aboriginal person was required to go to war, despite the existence at the time of conscription. Many First Nations men were turned away from the recruitment office due to the colour of their skin.

Williams says it was only a self-serving reflex that eventually inspired the government to recruit Indigenous servicemen, born of the fear that fighting would eventually reach Australian shores.

"It's very, very difficult to get beaten on your home turf if you know it, and who knows Australia better than Aboriginal people?"

Ironically, it was precisely this truth that saw the communist North Vietnamese forces triumph over their American-backed rivals in the south, an astounding David and Goliath story.

Despite the loss, which Australia shared, Mr Williams was thankful for the belated countenance of the army, navy and airforce, and the abilities they afforded him and other Blak servicemen.

"It gave us other skills that we needed to... help run our communities."

He said the brutal realities of war dispense with the racial hierarchies created at home.

"Bullets don't give a rats what colour you are. It takes some people a long time to learn that."