CAN AUSTRALIA LEARN FROM AMERICAS LYNCHING PAST?

Written By: Ross Turner

Edited By: Jack Latimore

Produced By: Jack Latimore & Daniel Gallahar

On top of a hillside in Montgomery, Alabama, a number of prominent buildings sit: buildings integral to the story of the United States. With its high white dome and marble stairs, the state’s Capitol building is resplendent, a monument to the city and state’s history as the capital of the breakaway southern states during the early stages of the American Civil War.

Alabama Capitol Building (Ross Turner)

Alabama Capitol Building (Ross Turner)

Yet, it’s not this building that draws tourists to the city. Nor is it the former Confederate States’ White House which is situated just a few hundred metres away. Instead, a memorial atop another hill, less than a mile away, is pulling the crowds: a memorial to the 4400 African Americans victims of lynching. Many of them brutally murdered simply because of the colour of their skin, or perhaps for how they looked at a passing white woman, or even simply because they told children to stop throwing rocks at them in the street.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened in 2018 and its impact on Montgomery has been telling. With manicured lawns, meandering pathways and peaceful waterfalls, it would be easy to forget that you are in the heart of a bustling city, let alone at the centre of a memorial for horrific crimes against humanity, but this space is changing people’s hearts and minds, and is quickly becoming the place that residents and the city’s tourist board actively recommend. For locals, the memorial has become a place of pride as they try to cast off the shadow of the city’s brutal slave trade and embrace its dual history of the civil rights movement.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice (Equal Justice Initiative/Human Pictures)

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice (Equal Justice Initiative/Human Pictures)

The man behind the memorial is human rights attorney and CEO of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Bryan Stevenson. It was through his work defending inmates on death row in Alabama that Stevenson saw an ever increasing need to tell the truth of racism and injustice that afflicts the United States.

“We're here in Montgomery where the community is littered with the iconography of the Confederacy. Where we glorify the period of time where black people were enslaved,” says Stevenson. “We make it sound triumphant and wonderful when it was brutal and horrific. And so, we have to tell the truth about that.”

Stevenson looked to other memorials around the world for inspiration as to how the Memorial for Peace and Justice could be received.

Bryan Stevenson (Rog and Bee Walker for EJI)

Bryan Stevenson (Rog and Bee Walker for EJI)

“In Germany, you can't go 200 meters without seeing the markers or the stones that have been placed next to the homes of Jewish families that were abducted during the Holocaust. The Germans actually want you to go to the Holocaust Memorial,” he says.

“When I got to Berlin, the cab driver says, ‘Oh, go to the Holocaust Memorial’. The hotel operator says, ‘Go to the Holocaust Memorial’. They don't want to be thought of as Nazis and fascists.

“But in the United States we haven't talked about slavery. We haven't talked about lynching, we haven't talked about segregation. And that has to change. And that was very much the motivation for creating this Memorial to honour the thousands of African Americans that were battered, and bloodied, and lynched, and burned, and drowned during that horrific era of terror,” says Stevenson.

His efforts haven’t been in vain. The multi-million dollar memorial has already drawn in more than half a million visitors in its first year of operation, and it’s not looking like numbers will slow down. However, it’s not the only destination in town attracting tourists in droves.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice corridor #2 (Equal Justice Initiative)

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice corridor #2 (Equal Justice Initiative)

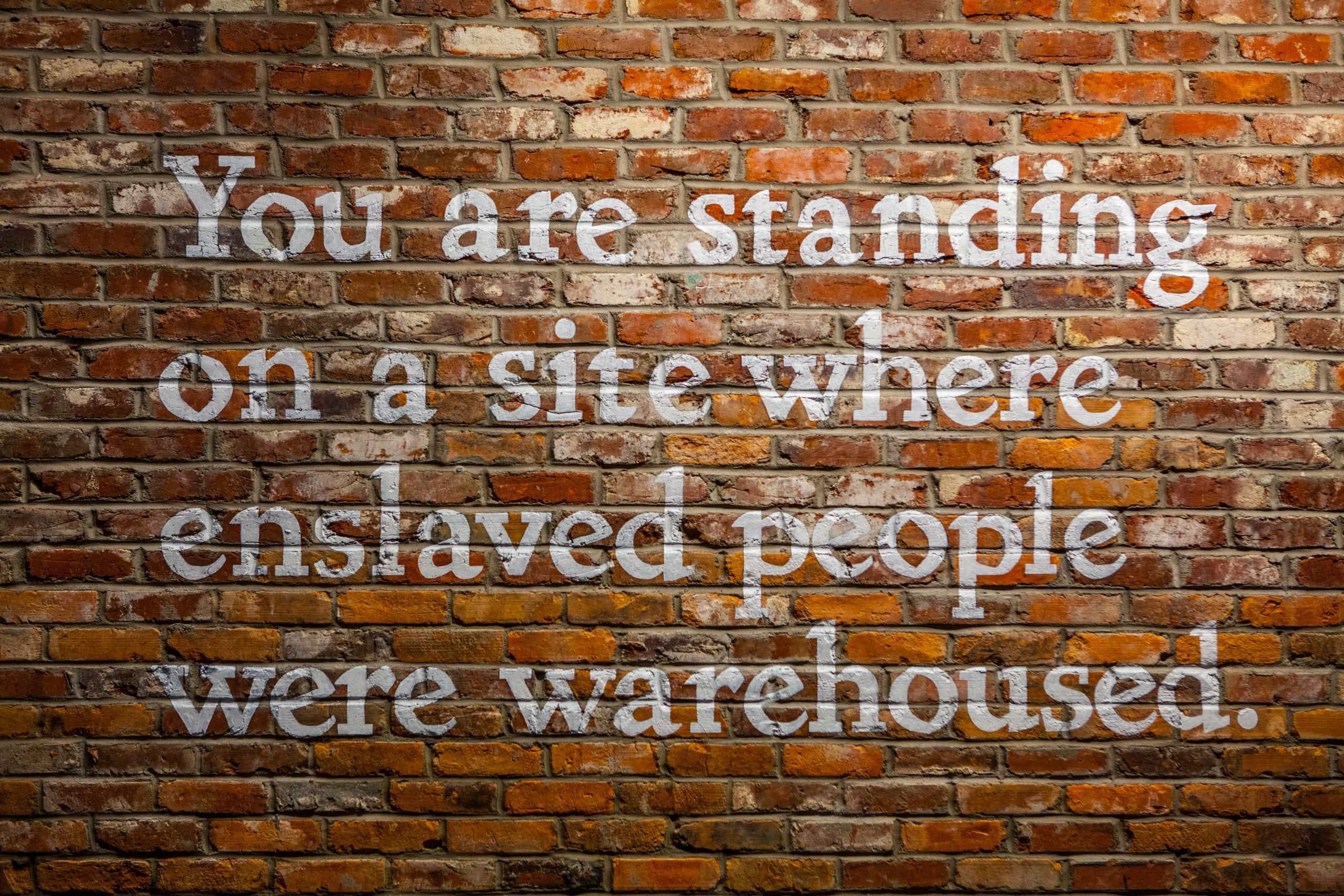

The Legacy Museum, housed in the basement of a slave storage building next door to Stevenson’s offices at the Equal Justice Initiative, pays homage to the thousands of African Americans who were transported as slaves through Montgomery. And it was while touring this second museum and using the interactive maps that highlighted the counties across the United States where lynching’s took place, that I pondered the question: Why hasn’t Australia got something like this?

Why hasn’t Australia got a space dedicated to the violence and brutal murders of its First Nations people during its Frontier Wars?

On returning home to Australia, I put the question to Professor John Maynard, a Worimi man from the Port Stephens region of New South Wales. Maynard says that frontier violence is a part of Australian history that is still swept under the carpet and that many people aren’t willing to face up to it yet.

Professor John Maynard

Professor John Maynard

“People have this idea that that there was no war here, no massacres here, but all the evidence is overwhelming. The old people can take you out to these sites, and can tell you the stories of these sites,” he says.

Journalist Lorena Allam, a Gamilaraay and Yawalaraay woman, feels like more needs to be done to change the narrative on the coverage of the Frontier Wars in Australia. In her Walkley award winning online series, ‘The Killing Times’, Allam set out to highlight research conducted by the University of Newcastle which involved mapping significant massacre sites across Australia.

“I always knew about what happened to our mobs, including my own and the neighbouring mobs, because our families talked about it,” says Allam. “But it was never discussed in public, certainly by the colonizers if you like. People just didn't want to face up to the truth of it.

Lorrena Allam of The Guardian

Lorrena Allam of The Guardian

“So that's why I wanted to do this project, it was to bring to light all the stories that we knew and the plenty more that we didn't know the extent of, and put it on the map so when you look at it, you grasp the enormity of this history.”

Pointing out that the projected numbers of Aboriginals killed in the Frontier Wars was, even at conservative estimates, said to be at over 20,000 dead, Professor Maynard describes the massacre maps project as a critical initative. Like Allam, he too says more needs to be done to properly acknowledge these massacres in a national space within Australia and he believes there is definitely an appetite in Australia for the development of one of these spaces.

“Myall Creek is a stand out example for this in Australia. The crowds turning up to remember this event are getting bigger and bigger every year, and it’s people who are coming there to recognise and pay their respects to what happened on that site and that past history,” he says.

Myall Creek Massacre memorial.

Myall Creek Massacre memorial.

“Myall Creek is probably the best other alternative [to Canberra]. The community up there, both black and white, have already been trying to get a memorial and centre built … I think that would be the right place to recognise these events. But it would be crucial to speak to the people up there and make sure that that is what they would want.”

Professor Lyndall Ryan, who leads the Massacre Map research project at the University of Newcastle, says she hopes that one day there will be a national memorial in Australia, one where the project’s maps can help Australians reflect on the nation’s brutal history.

“I'd like to see the massacre map, as … the beginning of a major Memorial,” she says.

Lyndall Ryan (Rolla Films)

Lyndall Ryan (Rolla Films)

“I think that local communities are coming together to erect memorials to particular incidents of massacre, and I think that's going to be the ground-swell to prepare a national memorial. And I think over the next five years, we will see such a memorial emerging in Canberra. There's certainly been a lot of lobbying for the Australian War Memorial to acknowledge the frontier wars, but I think, also, a separate Memorial needs to happen. And I think, as more information becomes available, as we get more massacres onto the map, that it will be an issue that people can no longer walk away from.”

The lobbying for the Australian War Memorial (AWM) to recognise the Frontier Wars has intensified each year over the better part of the last decade, particularly around the time of key dates such as Anzac Day and Remembrance Day.

The Australian War Memorial (Capital Photographer)

The Australian War Memorial (Capital Photographer)

In a statement to NITV News, the AWM stated its role is to “tell the stories of service to our nation in war and on peacekeeping and humanitarian operations.” It says this role is supported by its ‘Collection Development Plan’.

“As part of this plan we will be increasing our colonial period collection holdings, particularly relics and works of art related to frontier violence.

“Developing the Memorial’s collection to reflect this period will assist the work already under way in communicating the commitment displayed by Indigenous peoples to the defence of Australia. The Memorial strives to honour their ongoing service and sacrifice.”

The Museum went on to say that its “position on the violent, tragic confrontations that occurred in the course of Indigenous dispossession during the 19th and 20th century frontier violence is a matter of public record and can be found here”

But Allam thinks the AWM can do better.

“The Australian War Memorial needs to acknowledge this history [and] that more people lost their lives on this country than in any of the wars overseas,” she says.

“I think a national memorial to the people who lost their lives in in the massacres in this country would be an important and really empowering place for our mob to go and mourn and take strength from our shared history.”

Back in the United States, the Equal Justice Initiative says that despite the opening of memorials and the emergence of a national platform, more still needs to be done to acknowledge the USA’s own brutal past. One of the Initiative’s plans is to install memorial sites of lynchings across the nation, with markers that match those on display at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

The Legacy Museum lobby (Equal Justice Initiative/Human Pictures)

The Legacy Museum lobby (Equal Justice Initiative/Human Pictures)

Trey Walk, a Justice Fellow at the Initiative centre, is hopeful that many towns across the States would embrace their history, and will install these matching markers as a way to acknowledge this.

“We’ll be rolling this initiative out in the coming year, and any town or county that wants a marker is very welcome to have one. We want to tell the truth and share the truth to help this nation heal and come to terms with its past,” he says.

However, Prof Ryan notes that lynching and slavery memorials don’t take into account the brutal history experienced by the native American people right across the north American continent.

“There certainly could be a map compiled in the United States of massacres of Native Americans. And I would like to see that happen, and stretch that across into Canada as well,” she says.

So, the question should be asked: if Australia is to ever establish a memorial to those killed and murdered in the Frontier Wars, who or what body is going to be the one to set it up? And can Australians really learn from work such as that performed by Bryan Stevenson, who saw the need for truth-telling through the creation of memorials in order to help his nation heal?

Prof Ryan says she thinks that for change to really come in Australia that a massive groundswell of opinion or initiative is likely to be what causes politicians to act on the matter. While Prof Maynard says that it's critically important for the country to have a place of healing and reflection for the country. And to be able to reach that point, the nation has to look to the past and share that past to have a stronger future.

“We have to get through that process, it’s vital. To be able to heal and move on would be a wonderful thing” he says.