Olkola is the language spoken by the Olkolo or Koko-olkola' people of the Cape York Peninsula in Australia's north.

Like many other Aboriginal languages, Olkola is endangered.

“Over the years unfortunately speakers have diminished, and when there are fewer people speaking a language, obviously that language can slowly atrophy,” French-Italian linguist Sophie Rendina tells SBS Italian.

It is not an isolated case. Of the over 300 Indigenous languages which existed before Australia's colonisation, nowadays fewer than 150 remain, among which 90 per cent are at risk, and fewer than 30 are regularly spoken by Aboriginal people.

“In Australia, as in many other countries in the world, many people were punished physically because they spoke their own language," Rendina explains, "and they were separated from their families and communities to ensure that the transmission of their language and culture did not happen.”

This was part a policy implemented by the Australian government for many decades, which aimed to progressively weaken Indigenous culture until it disappeared.

The purpose of centres like the Pama Language Centre where Sophie Rendina works is helping Aboriginal communities recuperate and revitalise their own languages. These initiatives often come from within the communities themselves, as in the case of the Olkola Corporation, which has sought support to begin a path of the reinvigoration of their language.

“I believe it is important that whatever linguistic work is done stems from the community itself and is conducted ethically, respecting the community's aspirations, and that the various phases of the project are decided by the community," Rendina adds.

Recovering a language and contributing to its 'awakening' is a long and difficult process, but has big potential impact.

“It is a strong message of self-determination, which rebuilds the stories that are part of the cultural past of the group and of this community, which self-identifies around a common language which it does not necessarily speak anymore, but that it would like to find again, rebuild, reuse,” says the linguist working in community.

Rendina adds that nowadays there is a strong focus on the "important links between language, culture, and personal wellbeing, especially for these Aboriginal communities that are often remote and often marginalised.”

Rendina herself does not yet speak the language, but her aim is to facilitate the development of resources that will allow new generations to learn Olkola.

In the case of Olkola speakers a diaspora has developed, meaning people who speak the language live far from each other, but the project aims to create summer camps for young people on their ancestral lands, to make sure that this language and its sister languages, Uw Olgol and Uw Oykangand, are learned again.

The phonological aspect - literally determining how the language sounds outside of the written word - is one of the main hurdles Rendina is tackling.

“I am lucky to have some recordings from the '60s, '70s and '90s, and some linguistic notes from a couple of linguists. These are sources I can use as a stepping stone,” Rendina explains.

Leggi anche:

Imparare una lingua Aborigena: il Gupapuyngu

According to Rendina, revitalising Aboriginal languages is extremely important, "because diversity is a richness for all of us, and it is very important for both individuals and communities, which, by recovering their languages and access to their own culture, can improve their well-being.

“Through a language you can improve a person's self-esteem, and how they see themselves. It is not only a cultural process, but also a project for social well-being and for the well-being of individuals.”

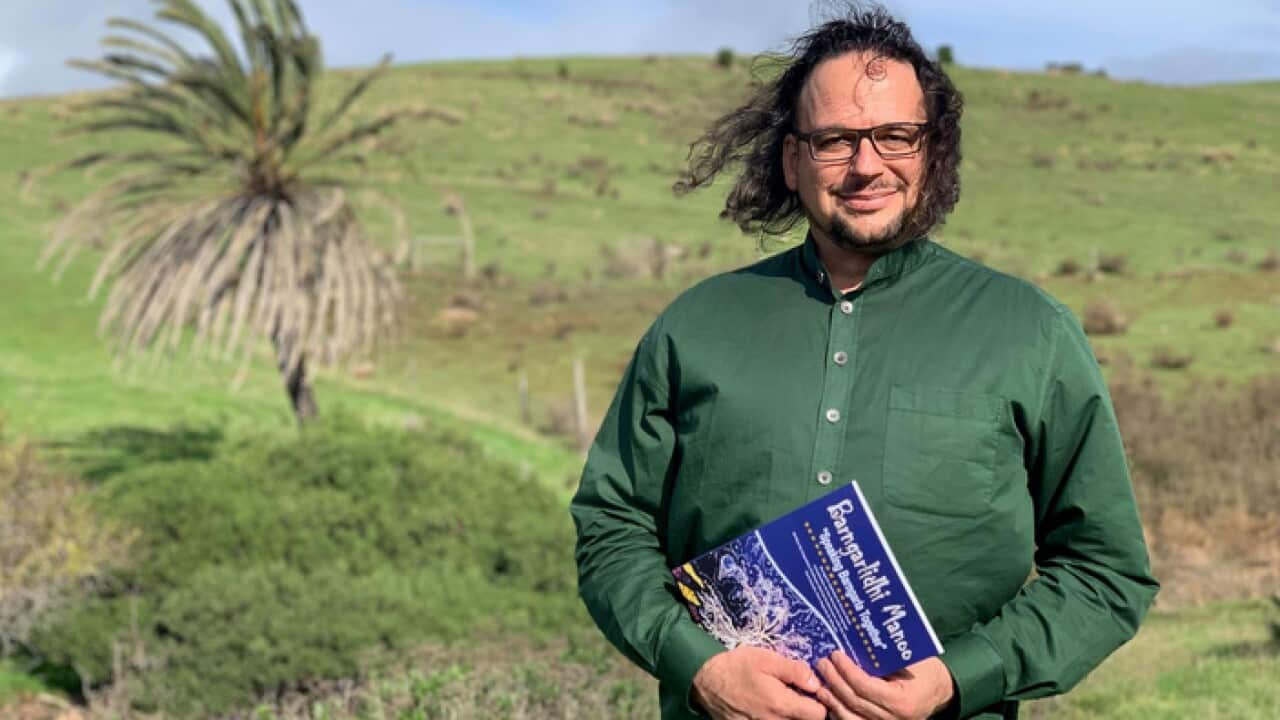

Image

Leggi anche:

Imparare una lingua Aborigena: il Barngarla