Vaega 'Autu

- O aia i fanua, e mafai ai ona toina 'ele'ele i lalo o pulega a le malo, e le aofia ai 'ele'ele umia ma'oti, e fa'aaoga e tagata Aboriginal ma Torres Straits mo sauniga fa'aaganu'u ma atina'e o le tamao'aiga.

- O aia i fanua, pule i fanua, ma isi fa'auigaina fa'aletulafono o aia tatau a tagata muamua i fanua, e 'ese'ese o latou fa'auigaina, ae 'auga e tasi i le fa'amoemoe e mauaina ai e Tagata Muamua le aia e faia ai tonu i mata'upu e patino ia i latou ma fanua.

- Na amata i fa'aaliga e pei o le Wave Hill i le 1966, le Walk-Off na soso'o ai ma ni tulafono taua e pei o le Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, ae o loo fa'aauau pea e o'o mai i aso ai.

- O a aia tatau a tagata Aboriginal i fanua?

- Na fa'apefea ona amata aia tatau a tagata Aboriginal i fanua?

- O a mea e aofia i aia tatau a tagata Aboriginal i fanua?

- O le a le 'ese'esega i le aia tatau a tagata Aboriginal i fanua, pule i fanua, ma se feagaiga?

- Aisea e taua ai le aia tatau a tagata Aboriginal i fanua i aso nei?

- Se fa'ata'ita'iga: Darkinjung Aboriginal Land Council

- O a ni lu'itau o i luma mo aia tatau a tagata Aboriginal i fanua?

- Aisea e taua ai aia tatau a tagata muamua i fanua mo tagata uma i Ausetalia?

O a aia tatau a tagata Aboriginal i fanua i Ausetalia?

I le tele o tausaga o so'otaga o tagata Aboriginal ma atumotu Torres Straits i o latou fanua ma 'ele'ele e le'i aloa'iaina. O tulafono o aia tatau i fanua, na fa'avaeina e tu'uina ai le pule i lalo o le tulafono i tagata muamua mo fanua e fa'asino ia te i latou.

Ae le'i taunu'u mai papalagi, e faitau afe tausaga o tausi mea tagata Aboriginal ma atumotu Torres Strait i o latou lava fanua ma 'ele'ele.

O pulega fa'akolone ia na faoa ai fanua e aunoa ma se maliega, na fa'avae i se taitonuga sese e ta'ua o le terra nullius — o lona uiga "o fanua e leai seisi e pule ai."

Na fa'apefea ona amata aia tatau a tagata Aboriginal i fanua?

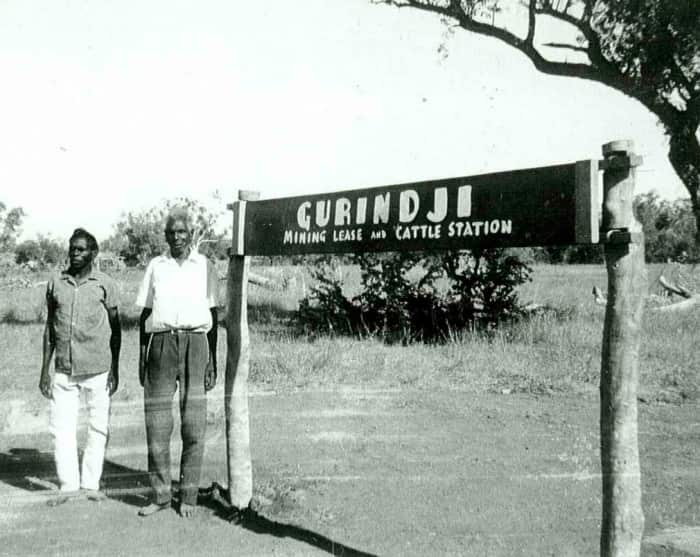

O aia tatau i fanua e pei ona iloa ai i aso nei, na amata i se tete'e, le Wave Hill Walk-Off i le 1966 — o se savali tete'e a tagata faigaluega Aboriginal Gurindji i se fa'atoaga povi i le Northern Territory. O le tete'e lenei na fa'avae i le tulaga fa'aletonu ma le talafeagai o galuega ae soso'o ai ma le vala'au e toe fa'afo'i mai o latou fanua.

O le palota fa'alaua'itele le referendum o le1967 na tu'uina ai le aia i le Malo Ausetalia e faia ai tulafono mo le manuia o tagata Aboriginal ma atumotu Torres Straits. O i'ina na mafai ai ona pasia le tulafono le Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 — o le tulafono muamua lea ua aloa'ia ai aia tatau a tagata muamua i o latou fanua.

O nisi o setete ma teritori e iai a latou lava tulafono e fa'atatau i mata'upu i aia tatau i fanua, ae le o iai se tulafono i fanua e ta-aofa'i uma ai Ausetalia.

O a mea e aofia i aia tatau a tagata Aboriginal i fanua?

O aia tatau i fanua e na o 'ele'ele e pulea e malo e mafai ona aofia ai - e fa'aigoaina o Crown Land - e le aofia ai fanua pulea ma'oti. O fanua e toe fa'fo'i i tagata muamua e le mafai ona latou fa'atauina atu pe lisi i se mokesi i nisi tagata. O fanua e avea ma esetete tausi mo Tagata Muamua e tausimea iai ma faia iai fa'ai'uga i auala e fa'aaogaina ai.

O pulega 'land councils' na fa'avaeina e avea ma sui o tagata Aboriginal ma atumotu Torres Straits e gafa ma le pulea o fanua ua toe fa'afo'i i tagata muamua. O pulega nei e fesoasoani i nu'u ma alaalafaga o tagata muamua i le fa'aaogasauniga ma fa'amoemoe fa'ale-aganu'u, si'osi'omaga ma atina'e.

READ MORE

Explainer: The '67 Referendum

O le a le 'ese'esega o aia tatau i fanua o tagata Aboriginal, native title ma se feagaiga?

E ui ina tai tutusa, peita'i e 'ese'ese o latou uiga:

- Aia tatau i fanua: Tulafono e faia e malo e toe fa'afo'i ai nisi o vaega 'ele'ele o fanua Crown land i tagata Aboriginal ma atumotu Torres Strait, e tele ina pulea e land councils.

- Pule fa'a-aganu'u: Amana'iaina e le tulafono o aia tatau a nisi Tagata Muamua i fanua ma vaitafe i lalo o a latou tu ma aga'ifanua.

- Feagaiga: Maliega aloa'ia i le va o le malo ma Tagata Muamua. O atunu'u e pei o Aotearoa Niu Sila ma Kanata ua iai feagaiga - e le'i iai se feagaiga i Ausetalia nei.

Aisea e taua ai aia tatau a tagata Aboriginal i fanua i aso nei?

O le toe fa'afo'i o fanua ma 'elele'ele, e toe fausia ai so'otaga o tagata muamua i le gagana, aganu'u ma le Country. E fesoasoani ai i mata'upu e pei o a'oga, soifua maloloina ma le tuto'atasi i le atina'e o le tamao'aiga.

E pei ona fa'amatalaina e Dr Virginia Marshall, o se fafine Wiradjuri Nyemba:

“The water speaks to us or the trees speak to us, but we don't need to take on a Western environmental ideology… Our law and our creation stories guide our understanding.”

Se fa'ata'ita'iga: Darkinjung Land Council

O le Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council, na fa'avaeina i lalo o le New South Wales Aboriginal Land Rights Act.

E manatua e Uncle Barry Duncan, o se tamaloa Gomeroi lona amataga i le 1983:

“It brought this community together. It was a way of getting land invested back into Aboriginal ownership.”

“Now people know… we were very wise and smart with the land holdings.”

Subscribe to or follow the Australia Explained podcast for more valuable information and tips about settling into your new life in Australia.

Do you have any questions or topic ideas? Send us an email to australiaexplained@sbs.com.au