Tasmania, known to its First Peoples as lutruwita, has long been a flash point in Australia's environmental struggles — from logging and mining to water protection.

Now, a new generation of palawa Aboriginal leaders is stepping up, continuing an ancient legacy of defending Country in the face of environmental destruction.

In Tasmania, logging is a billion-dollar industry that supports over thousands of jobs and exports millions of tonnes of timber, woodchips and pulp overseas, primarily to feed paper mills in China and Japan.

But as vital carbon sinks and biodiversity havens shrink, Traditional Owners argue that the long-term environmental and cultural costs are far greater than the economic gains.

Among them is 25-year-old palawa lawyer Maggie Blanden. Last year, she made headlines by rejecting her nomination for Young Tasmania of the Year to protest a date — 26 January — which she said represents genocide and stolen land.

Blanden told NITV's The Point that she was raised with an understanding of both Aboriginal lore and "settler" systems and is training to be a lawyer to challenge colonial structures from within.

"Education is power for our mob," Blanden said.

"Our old people were on the front line defending Country and that legacy continues today. They were protesting for their inherent rights to be Aboriginal people and to be on Country and yet they were being persecuted for it.

"Becoming a lawyer was my part in that, breaking down those systems and really bringing us home to that key message."

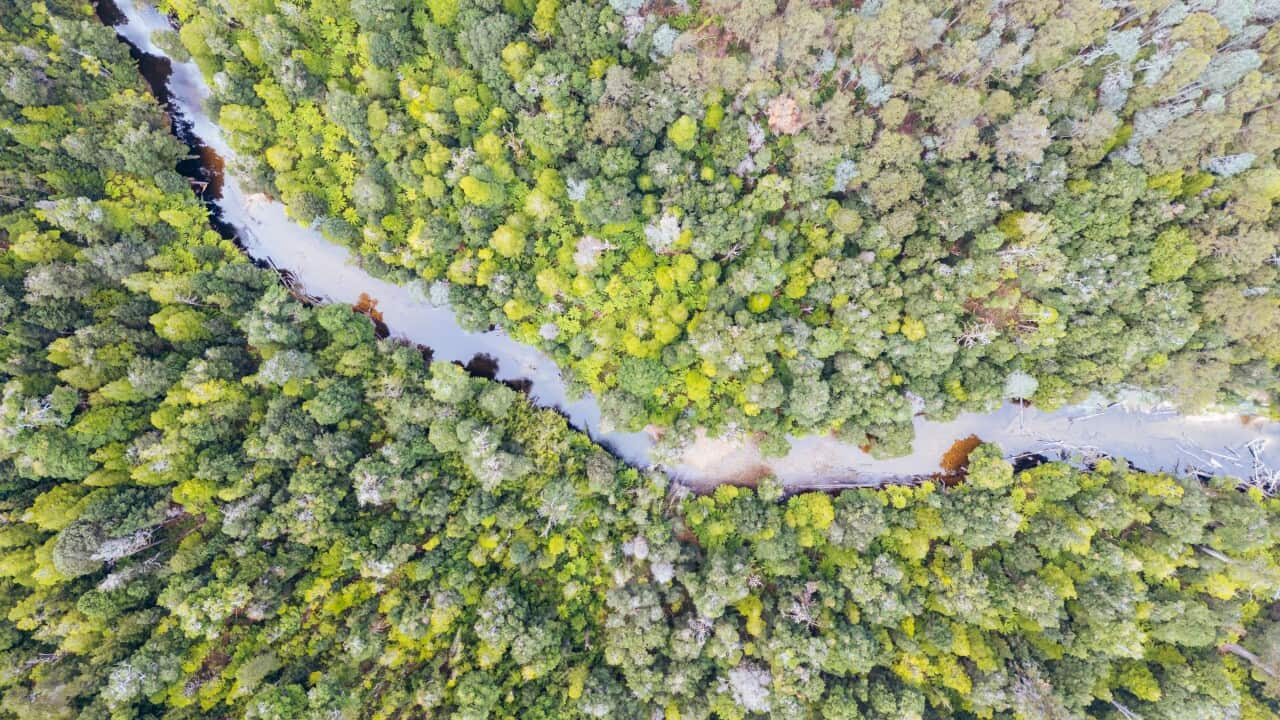

It's a message that echoes across places like the Styx Valley, a stronghold of Tasmania's ancient forests and a hotspot for protests against logging.

Every day vital carbon sinks and biodiversity havens shrink as forests are reduced to woodchips that are shipped offshore to become paper and fill the trays of the world's photocopiers.

It's an industry that supports over 5,500 jobs and contributes $1.2 billion to the economy, but Traditional Owners argue that the long-term environmental and cultural costs are far greater.

Ruth Langford, a Yorta Yorta and Dja Dja Wurrung woman born in lutruwita, is one of the cultural caretakers fighting back.

"It's not actually a forest, it's a plantation. It's a single species tree," she said, gesturing to rows of identical trees.

"This is very sick country.

"The concern that we have is these types of plantings create potentially catastrophic bushfires, as well as it's sucking all the water up."

The state government's Sustainable Timber Tasmania, formerly Forestry Tasmania, manages approximately 812,000 hectares of public production forest and promises a sustainable approach that is socially, economically and environmentally responsible.

Some 1.2 million hectares of the state's forest is classified as old growth, of which eight per cent faces potential logging within the 'Permanent Timber Production Zone'.

Every three years, the government releases a forestry plan that designates large areas for logging that include a patchwork of plantations and old-growth forests and there are fears that more protected areas could be opened up to potential logging.

Langford says contractors often have little say in the areas they are harvesting, and many taxpayers are asking why they are continuing to foot the bill for an unsustainable approach.

"It doesn't make economic sense," she said.

"The government is subsidising all the roads, all the departments, and loses all of our carbon, loses all of the biodiversity, all of the water catchment and loses the very potential of what this could be both for timber production and also for future generations."

Palawa woman Carleeta is part of a protest camp in Styx Valley and believes balance is possible and immediate change essential.

"We're not saying completely stop the whole logging industry," she said.

"We need to go more towards different plantations and alternatives to logging these beautiful old-growth forests that have seen, not only our old fellows, but will see our future generations be able to come and sit under these same trees that their ancestors sat under."

At the heart of the movement is a deep reverence for inter-generational responsibility. For Blanden, elders like Uncle Jim Everett (Puralia Meenamatta), who still physically defends forested areas, represent that legacy.

"He always says it's not about land rights — it's about the land's right. The right to be cared for. That's what we carry on our shoulders," she said.

As climate change accelerates and biodiversity collapses, Blanden sees Aboriginal leadership as vital.

"They need us. Country needs us and it is our time to answer that call and come and protect Country."

The Point airs Tuesdays 7.30pm on NITV, and is available after the broadcast on SBS On Demand.

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.