Before they got married, Wan and Li (not their real names) discussed having children. They came to the same conclusion — it wasn't for them.

So earlier this year, 30-year-old Wan got a vasectomy. Then Li posted about the experience on social media.

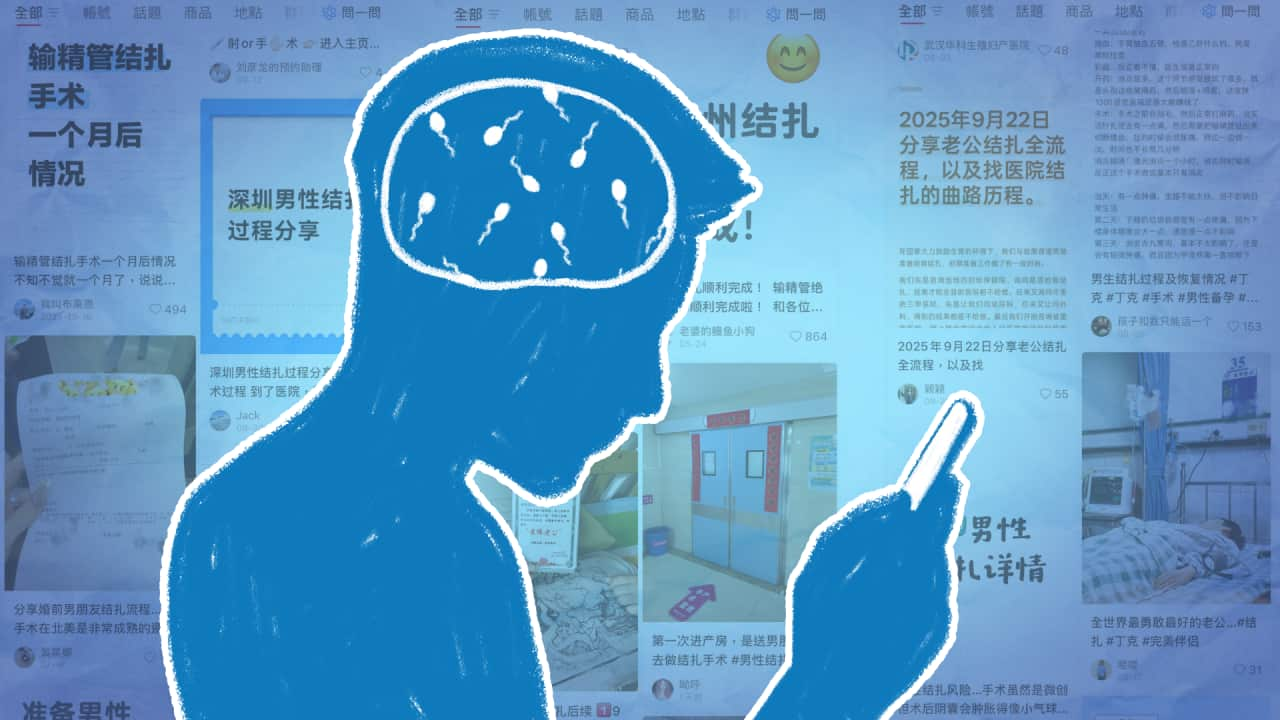

It might seem unusual to document such an intimate procedure online. But if you scroll through Chinese social media platforms, you'll find video after video about people getting vasectomies.

"My husband simply does not like children," Li, 27, told SBS Chinese and SBS Dateline.

Wan said he often has trouble controlling his emotions when children are "noisy or annoying".

For Li, not wanting children stems from a mix of her strict childhood and a desire not to lower her "quality of life".

"I just want to live better for myself now and make up for what I missed in my childhood," she said.

But in a country of about 1.4 billion people still grappling with the lingering ramifications of the one-child policy, including an ageing population and declining birth rate, the government sees young people procreating as essential. This has resulted in a reduction in birth control procedures like vasectomies.

An ageing population and a falling birth rate

According to official government figures, from 2018 to 2019 there was a significant reduction in the number of vasectomies — from 53,128 to 4,742.

China stopped providing statistics on 'family planning' procedures after 2020. The Washington Post reported in 2021 the Chinese government had started cracking down on the surgery in an attempt to raise the birth rate. This also aligns with Wan and Li's experience, as they struggled to find a hospital willing to perform the procedure.

Other data shows that for the past three years, China's population has been decreasing.

In 2022, the population fell for the first time since 1961, during the Great Famine. An estimated 30 million people starved to death during the famine, which lasted from 1959 to 1961. It's widely regarded as the largest famine in human history, and a 'man-made' disaster — the unintended result of Chairman Mao Zedong's Great Leap Forward modernisation program.

China's fertility rate has also been consistently decreasing since the early 1960s, reaching a low in 2023 of one birth per woman.

The key factor in China's reduced fertility rate is the one-child policy; implemented between the late 1970s and 2015 to help rein in the then-rapidly growing population.

In the 10 years since the policy ended, the government has introduced 'two-child' and 'three-child' policies to address the now-falling birth rate and ageing population. This combination has led to serious concerns about the country's shrinking labour force. The increasingly older population will also require higher levels of social support, including reliance on an underfunded pension system.

According to the World Health Organization, by 2040, 28 per cent of China's population will be over the age of 60 due to factors like declining fertility rate and longer life expectancy.

This is now a focus of the Chinese government. In a 2023 discussion with All China Women's Federation, a state-sponsored organisation, President Xi Jinping said it was necessary to "actively cultivate a new culture of marriage and childbearing".

Impacts of the one-child policy on young people

In the one-child policy era, families with more than one child were forced to undergo sterilisation. Millions of women were subject to this and to forced abortion. To a lesser extent, men were forced to have vasectomies.

According to government statistics shared in 2013, since 1971, doctors in China had performed 336 million abortions and 196 million sterilisations of both men and women.

Dr Stuart Gietel-Basten, professor of social science and public policy at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, said we don't know what the "long-term psychological internalisation" of the one-child policy will be. But it would be understandable if the messaging has "sunk in somewhere".

"If you spend 35 years telling people one child is good ... and if you have more than one child, then life is going to become more complicated. Then all of a sudden you actually say, 'Yeah, no, have three children actually, now three children is good, you should have three children', then that kind of messaging can be tricky."

The factors influencing young people to get vasectomies

Li said she hasn't seen many other people posting about getting vasectomies. Her motivation in posting about Wan's was to challenge stigma around the procedure.

She thinks "many people" might have had the surgery but don't talk about it.

Li also often gets comments and DMs from people saying they didn't know people got vasectomies. Some ask which hospital they went to.

When they first contacted hospitals, they were told they would only be approved for a vasectomy once they had a child. The surgeon who performed Wan's vasectomy told them he only agreed to do the surgery because he thought the couple already had children.

The couple also said it was easier to find a hospital willing to perform the surgery after they got married in late 2024.

Gietel-Basten said the fact vasectomy videos are being shared on social media might make it appear to be a "bigger phenomenon than it really is".

"However, even though it might not be very common, you can see why it catches on because it is part of this zeitgeist."

He compared the vasectomy trend online to the 'lying flat' movement, where young Chinese people reject the traditional expectation to work hard and pursue careers.

"It's like a kind of quiet act of rebellion," he said.

"To say, 'Well, the expectations of society for me are that I'm supposed to work crazy hard and now I'm being pushed to have children, where my family in the past were pushed not to have children ... and I just don't want to do it."

Part of the reason he thinks vasectomies have "captured the imagination" online is that for many young Chinese people "the prospects look a bit grim".

He said there hasn't really been a conversation around the barrier to having children.

"It's really a reflection of the challenges of contemporary society: finding a job and then finding a house, and then finding a partner who's going to share equally responsibilities with you, and then if you have a kid, what it means about childcare and what it means about education," he said.

"Until those things are addressed, then actually this pressure to have kids is not really going to do an awful lot."

There are also the pressures after having a child, like childcare and education, which he highlighted as particularly relevant in an East Asian context.

"That's one difference to Australia. Not just the financial, but the psychological burdens of pushing your kids to achieve what is seen to be extreme levels of education."

This is something that influenced Li's decision.

"I feel that my upbringing, and also the current education system, have made childhood quite painful in some ways," she said.

"If I became a parent, I might unconsciously set high expectations for my child because of the competitive environment and social pressure."

Gender dynamics at play

Li said perceptions among their peers of Wan's surgery differed depending on gender.

"When some women who are close to us heard about it, they said, 'Wow, your husband is amazing'. But for some men, it was the opposite."

Wan had to report the vasectomy to his workplace because of a family planning leave policy. The leave required multiple levels of approvals, as well as conversations with his supervisors and confirmation that both Li and Wan's families were aware he was getting a vasectomy. His supervisor also had to record meeting notes to show Wan been advised by his work not to have the surgery.

And as word of Wan's procedure went around the office, so did negative comments by his male colleagues.

"We heard rumours like: 'His wife must be really controlling — she forced him to do it'," Li said.

"In their mindset, no man would willingly choose to do this; it must have been the wife's decision."

For some young men in China, the decision to get a vasectomy — and then to post about it online — might stem from a desire to demonstrate a belief in gender equality. Gietel-Basten said the burden of long-term contraceptive methods has traditionally been on women.

"This is a way of offsetting the balance and demonstrating, 'Well, as a man, I'm going to take responsibility for this and I'm going to do my bit to make sure that in that relationship, effective long-term contraception is being used'," he said.

Official government figures show the number of birth control procedures performed on women, including 237,489 tubal ligations in 2019, down from 404,212 the year before.

And while there were 3,256,502 intrauterine contraceptive device (IUDs) removal surgeries that year, another 3,011,378 women had an IUD inserted.

When they went to the hospital for Wan's vasectomy, nurses asked Li why she wasn't getting an IUD instead.

"I was astonished — how could a healthcare worker say something like that?"

Fears for the future

There's also been some resistance from their families. While their parents have agreed to the decision, it is "reluctant".

Wan's mother will sometimes send him videos of babies, or articles which he thinks are an attempt to influence their decision.

"We have been very firm about it, telling them clearly that we are certain about not wanting children, and asking them to stop sending that kind of content," he said.

"They stopped for a while, but I can still sense that in their hearts, they want us to change our minds someday."

As for their own future — and China's ageing population, which has been broadly described as a demographic crisis — the couple aren't too concerned.

Li believes that as more people like them choose not to have children, and can't rely on immediate family support in old age, China's aged care system will improve. Wan acknowledged that with fewer people having children, China's labour force might shrink — but he thinks China's focus on robotics development will be a solution.

"As the population declines, robots will take over more tasks," he said.

Wan also believes that ultimately, if the birth rate does fall too low, the government will actively encourage people to have children through financial incentives.

"People like us are just a small portion. Some others choose not to have children for financial reasons, but once supportive policies appear, many will want to have them."

Additional reporting by SBS Chinese.

Dateline is an award-winning Australian, international documentary series airing for over 40 years. Each week Dateline scours the globe to bring you a world of daring stories. Read more about Dateline

Have a story or comment? Contact Us