On a clear afternoon in March this year, off a beach on the NSW south coast, Joel Trist and his mate, Brett, paddled out into the water for a surf in the still-balmy ocean.

Time passed. They caught a few waves. Shared some laughs. Then, just before 7pm, the unthinkable.

"All of a sudden I heard this terrible scream," says Joel. "I looked up and I saw all of this commotion going on, a lot of splashing, and I knew exactly what was happening ... He's getting attacked by a shark."

Trists' friend Brett had been savaged, sustaining life-threatening injuries to his leg.

"My first instinct was, 'I have to get over to him'," Trist tells Insight's Jenny Brockie, as the show looks at how people react in emergencies. "I think [escaping] did come across my mind for that split second. But just seeing everything that was going on at that time, I just thought I needed to get over there and help out."

The shark had bitten through Brett's leg rope, casting his board - and Brett - adrift. Trist managed to paddle him to shore, himself mostly in the water still.

"I have to admit, when I was paddling him in and we got caught in a bit of a rip, I was looking back and at that stage I could see the blood flowing out towards the sea when we were coming in. And I thought, there could be a chance it will come back here and have another go at us."

I knew exactly what was happening ... He's getting attacked by a shark.

Trists' reaction to immediately help is likely part of a personality type more associated with acting in a crisis - a 'fight' response in contrast to the 'flight' response many others with different personality traits would experience.

"People who tend to be a little bit more open to experience and certainly people a little bit more extroverted and impulsive tend to be more wired towards [acting]," says psychologist and lecturer Dr Rachael Sharman.

While Trist says he doesn't see himself as necessarily 'extroverted', he does connect with that distinction.

Sharman expands that these people usually recognise that they have something to offer, whether qualifications or previous experience in a similar situation, and that they already have some coping mechanisms in place to deal with the situation. The essential question we ask ourselves in a moment of emergency is, 'can I cope?' and personality usually answers that.

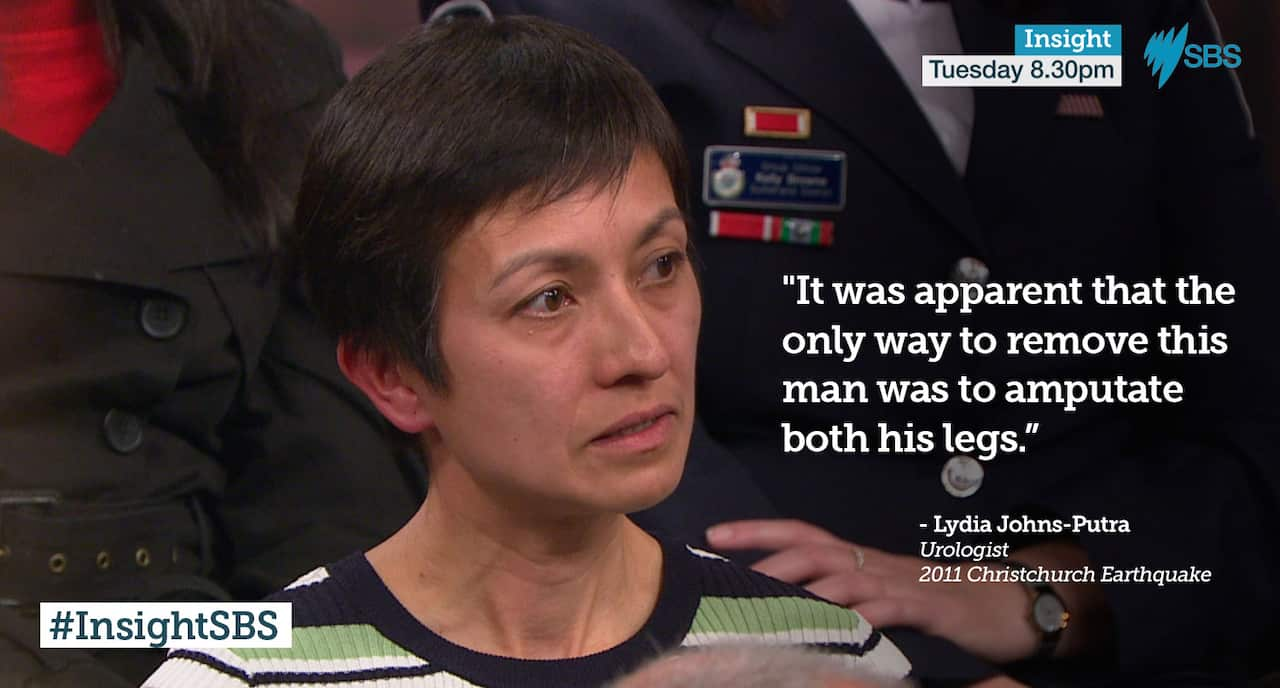

"I think I’m a calm person generally," says Lydia Johns-Putra. "I think surgical training does that to you. You have to make decisions sometimes and very often no decision is worse than any decision."

In 2011, Johns-Putra was in Christchurch, NZ, for a conference when a magnitude 6.3 earthquake tore down large parts of the city.

A urologist by training, she and other surgeons responded to the devastation, helping to free people trapped inside crumbled buildings. She ended up in the rubble, using a hacksaw and a Leatherman knife to amputate a man's legs.

Peter Davidson, a rescue paramedic who helped save eight lives during the infamous 1998 Sydney to Hobart yacht race, agrees that the ability to respond effectively grows with experience.

"Exposure and experience to those incidences that help you adapt and help you manage those crisis times," he tells Insight's Jenny Brockie.

Not everyone is as capable in their response, however.

Exposure and experience to those incidences that help you adapt and help you manage those crisis times.

Jessie Stephens was walking home with her sister, Clare, one afternoon when their paths crossed with a man walking in the opposite direction. Jessie made eye contact with the man, gave him a nod of acknowledgment - only for him to push her into a driveway, begin scratching her and putting his hands inside her shirt. As he stepped away from her again, he began to masturbate.

Clare's first instinct was to scream, and become verbally aggressive, but she found it hard to physically intervene. As she pulled out her phone to call the police, the man fled.

Following the ordeal, Jessie was astounded no-one had come to her aid. It had been 4pm in the afternoon, and both women noticed passers-by stop to watch or residents eventually come out of their houses.

It's likely some of those who witnessed the event were the kinds of people less predisposed to act in an emergency.

"People who are naturally a little bit more anxious, perhaps a little more neurotic, they tend to be more wired towards all of the bad things that will happen if they intervene," says Sharman.

Clare admits she was "definitely too scared and anxious to actually physically get involved."

Whether your personality is skewed towards an outgoing intervener or an introverted avoider, these emotions are "fairly primitive," according to Sharman.

"It comes back to basic fight or flight. People have to make a decision in this situation whether they’re going to approach something and try and fight it off, or avoid it and flee."

Hear these stories, and more, on Insight: First on the Scene | Catch up online now:

[videocard video="696180291883"]

Insight is Australia's leading forum for debate and powerful first-person stories offering a unique perspective on the way we live. Read more about Insight

Have a story or comment? Contact Us