Listen to Australian and world news, and follow trending topics with SBS News Podcasts.

TRANSCRIPT

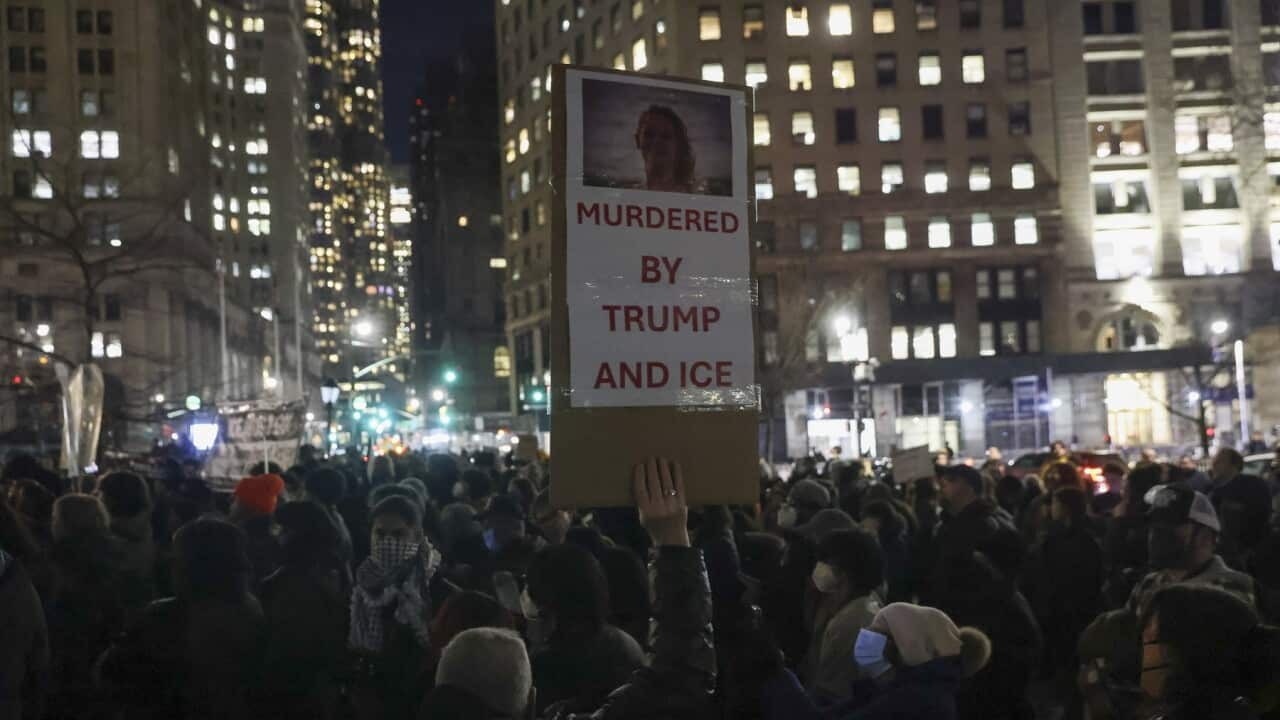

Over the weekend, thousands rallied across Australia in anti-immigration marches.

At the heart of the rallies was a call to end what protest organisers called "mass migration" to Australia.

Scientia Professor at the Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law Jane McAdam says the rhetoric at these marches focused on a key misconception- that migrants are to blame for a number of pressures impacting Australians.

Seen on banners, chanted in slogans and speeches at the rallies was the idea that high migrant numbers are responsible for rising cost of living, housing shortages and job insecurity, among other issues.

"Unfortunately, there's a lot of misunderstanding and misinformation out there about the links between migration, housing shortages, cost of living pressures, infrastructure, all those sorts of things. And I think that that has been exploited by certain elements of the community, particularly on the far right to suggest that migrants are taking your houses, taking your jobs, these sorts of things."

Global Migration expert and Associate Professor of Public Policy at the University of Sydney Anna Boucher says issues like the housing crisis and rising cost of living are undoubtedly impacting many Australians.

However, she says the idea that the fix for these pressures is to curb migration is misdirected, and misses the vital role migrants play in the functioning of Australia's economy and society.

"I mean 50 per cent of the Australian population are either migrant background or have one parent who was, so we're actually talking about most of Australia. In essence, Australia couldn't function without migration. International student migration comprise is a big component of our gross domestic product. Migrants provide necessary labor into skill shortage areas that we can't meet through domestic supply and immigration is a central component of Australia's multicultural identity.”:

The most recent ABS data shows migrants make up nearly one-third of Australia's workforce.

Australia's migrant population is also one of the most skilled among OECD countries, with nearly six in ten migrants holding a university degree or higher, in contrast with around four in ten native-born Australians.

Matt Grudnoff , Senior Economist at the Australia Institute says Australia relies on its skilled migrants to fill crucial gaps in the jobs market.

"So migrants tend to be younger than the average. Australian tend to be well-skilled and so they add a lot to Australia's economy. Australia's migration system in particular is very skills focused, so it tends to target migrants with skills that we have a shortage of. And so what they actually do is they enable us to continue to have access to goods and services that might otherwise be difficult to produce in Australia or would become far more expensive."

Migrants make up a particularly large share of the workforce in key industries such as hospitality, health care, professional services, manufacturing and administrative services.

According to 2021-2022 ABS jobs data, 15 percent of migrants in Australia work in the area of health care and social assistance, and the 2021 census shows more than 40 per cent of registered nurses and aged and disabled carers were born overseas.

Professor Boucher says with Australia's population aging, it's expected the country will rely heavily on migrant health workers in future.

With no current visa category for low-skilled migrants, she says changes may need to be made to enable more skilled and low-skilled migrants to fill gaps expected to grow in this industry.

"So yeah, it's clear that we won't meet the needs of our aging population exclusively through our domestic labor market... we will need to think quite carefully about how we bring in migrant labor whether that's forms of labor agreements as they're called, or whether there are changes to the visa structure to permit that to occur.”

Mr Grudnoff says one of the key messages voiced at the anti-immigration rallies over the weekend was a concern that mass migration numbers are to blame for the housing crisis Australia is experiencing.

He says there are a few key issues with this concern.

Firstly, Australia is not experiencing the historic surge in migration protesters and rally organisers claim.

While a slump in migration during the COVID-19 Pandemic was followed by an increase once borders re-opened, Mr Grudnoff says since 2024, population growth appears to have fallen back to pre-Covid rates.

He says the idea that the population is growing at a faster rate than housing is also not supported by the data.

"Over the last 10 years, the population has grown by 16%. So in order to just house that extra 16% of people, we'd need to increase the number of homes by 16%. But the number of homes has increased by more than 16%, it's increased by 19%. So we're actually building, so actually the number of homes is growing faster than the population."

He says lack of affordable housing Australians are experiencing is in part driven by tax laws which favor investors.

"There's been a big increase in demand for housing and in particular, investors demand for housing. So what's happened is the capital gains tax discount was introduced under the Howard government that has made making money out of housing very tax effective. It's encouraged lots of people to go out and buy an investment property. These people are outbidding first home buyers effectively and increasing price of housing and stopping people from getting into the housing market."

According to Mr Grudnoff, a lack of low-cost government housing is also contributing to the crisis.

"So one of the problems in Australia with our housing is that the government has withdrawn from the housing sector. We used to be in the sixties, seventies and eighties, the government was heavily involved in supplying public housing and now they've largely vacated that they're not building nearly as much housing. And so consequently there is a lot less of that housing available and this is adding to the affordability crisis."

Professor Boucher says as with other concerns over pressures like cost of living, it's clear blame for the housing crisis is falling in the wrong place.

"It doesn't mean that there might not be an issue with housing, but that needs to be addressed separately. And I think that's maybe the answer is more densification. Maybe it is a speeding up the rate of construction. Maybe it is different methods of urban planning. We have a very low density city for its population size in Sydney, for instance, if you compare it with comparable cities overseas. But that's a product of our poor planning, not of migrants."

Professor McAdam says while concerns people have about housing, cost of living and infrastructure can't be ignored, migration should be considered an important part of the solution, rather than the problem.

"So I think we really need to take a good hard look at the evidence when it comes to looking at what is driving those pressures and looking at how the government at all levels needs to be addressing things like the housing crisis without wrongly demonizing migrants in the process... Australia is a country full of migrants and it's migration that has made us and multiculturalism that has made us such a flourishing, diverse, and successful society and country that we are."