7 min read

This article is more than 7 years old

Country

Explainer

Drums and despair: Inside Canada's Pikangikum community

Pikangikum, a remote Ojibwa community in Canada, navigates its way through social, economic and health challenges.

Published

Updated

By Ali MC

Image: Pikangikum community council centre. (Ali MC)

Pikangikum First Nations community

In January this year, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made a rare visit to the northern Ontario First Nations community of Pikangikum, to speak with elders and community members.

The catalyst for the trip was the immense social challenges facing First Nations people living on the remote reservation: an epidemic of youth suicide, over-crowded housing, a lack of basic amenities, and the resultant mental health challenges. If it sounds eerily similar to the challenges facing remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Australia, so too is the history.

If it sounds eerily similar to the challenges facing remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Australia, so too is the history.

Housing in Pikangikum is grossly overcrowded. Around 3000 people live in the community in only 375 houses. Source: Ali MC

Indigenous peoples of both countries have been subject to a punitive colonisation typified by massacres, disease, child removals, land theft and a continued denial of human rights; in 2007, for example, both countries initially refused to sign the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

As a legal advocate at the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service in Melbourne, I had the privilege of visiting Pikangikum as a guest of Nishnabwe Aski Legal Services in August 2017.

Boardwalk built by young people in cooperation with the Pikangikum police. Part of a successful youth diversion program. Source: Ali MC

The challenges of Pikangikum

As we flew into Pikangikum in a light aircraft, I was astounded by the natural beauty; endless boreal forest, and natural, fresh water lakes glimmering in the summer sun all the way to the horizon. Such surrounds, however, means that Pikangikum is predominantly a fly-in and fly-out community; the only roads servicing the area are available in winter, when the lakes freeze up and the ice roads can be traversed.

Such surrounds, however, means that Pikangikum is predominantly a fly-in and fly-out community; the only roads servicing the area are available in winter, when the lakes freeze up and the ice roads can be traversed.

Flying over the boreal forest northern Ontario. For most remote First Nations' communities, an expensive charter flight is the only way in or out Source: Ali MC

Like Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Australia, such isolation means a lack of services such as medical care and mental health assistance.

Sadly, the month prior to my arrival had seen five young people commit suicide in Pikangikum; a community of less than 3,000 people.

Yet the resilience of the community is astounding. An astonishing 75 per cent of people in Pikangikum are under the age of 25, meaning that it is largely up to young people to overcome the challenges they face.

Yet the resilience of the community is astounding. An astonishing 75 per cent of people in Pikangikum are under the age of 25, meaning that it is largely up to young people to overcome the challenges they face.

The community centre is used as the courthouse. The fly-in court sits once a month, at great expense, the majority of matters heard are crimes of poverty. Source: Ali MC

The Pikangkum police station has seen more than one major protest. In 2016, the station was mobbed in outrage at a community member being unfairly tasered. Source: Ali MC

Single diesel generators and no access to running water

I am picked up from the airstrip and driven around Pikangikum by two youth workers, Darren and Ryan, who explain that the entire population live in only 375 homes.

Compounding the overcrowded homes, none of the houses have access to running water, despite being surrounded by fresh water lakes, which have been polluted by nearby mining companies.

Compounding the overcrowded homes, none of the houses have access to running water, despite being surrounded by fresh water lakes, which have been polluted by nearby mining companies.

Darren and Ryan from Nishnabwe Aski Legal Services, with Ali MC. It is often up to the young people themselves to find solutions to the challenges they are face Source: Ali MC

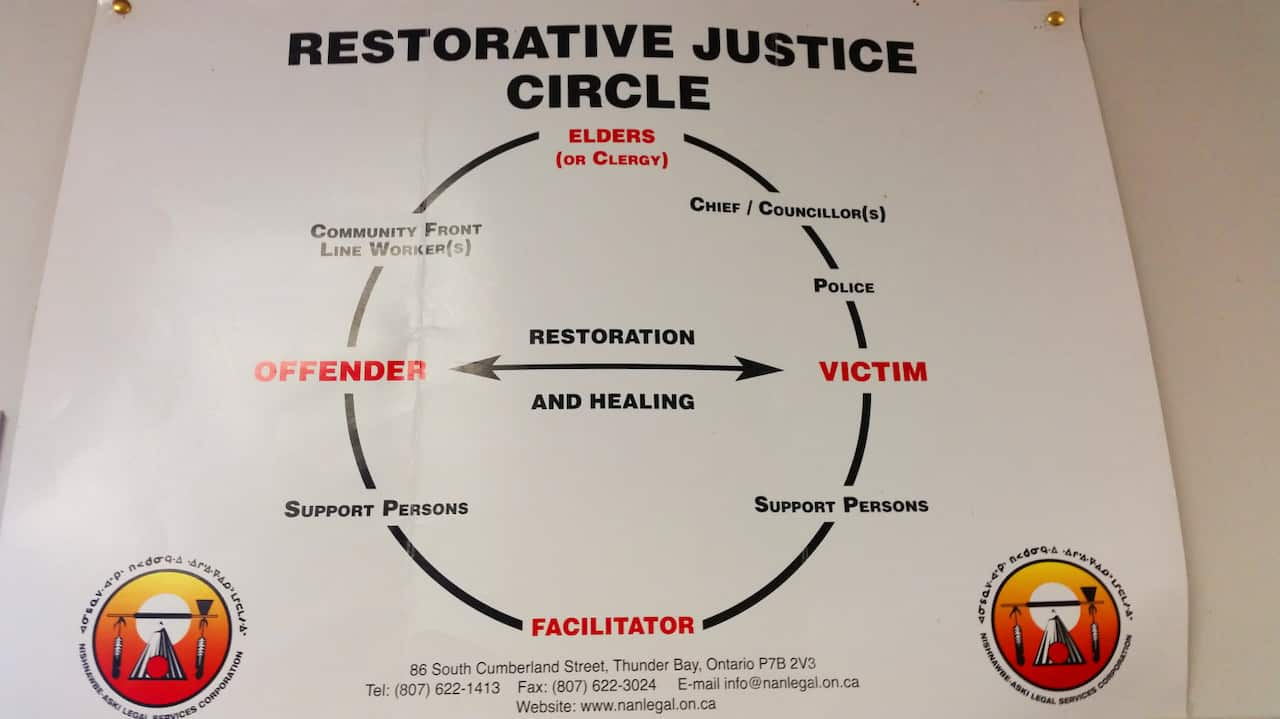

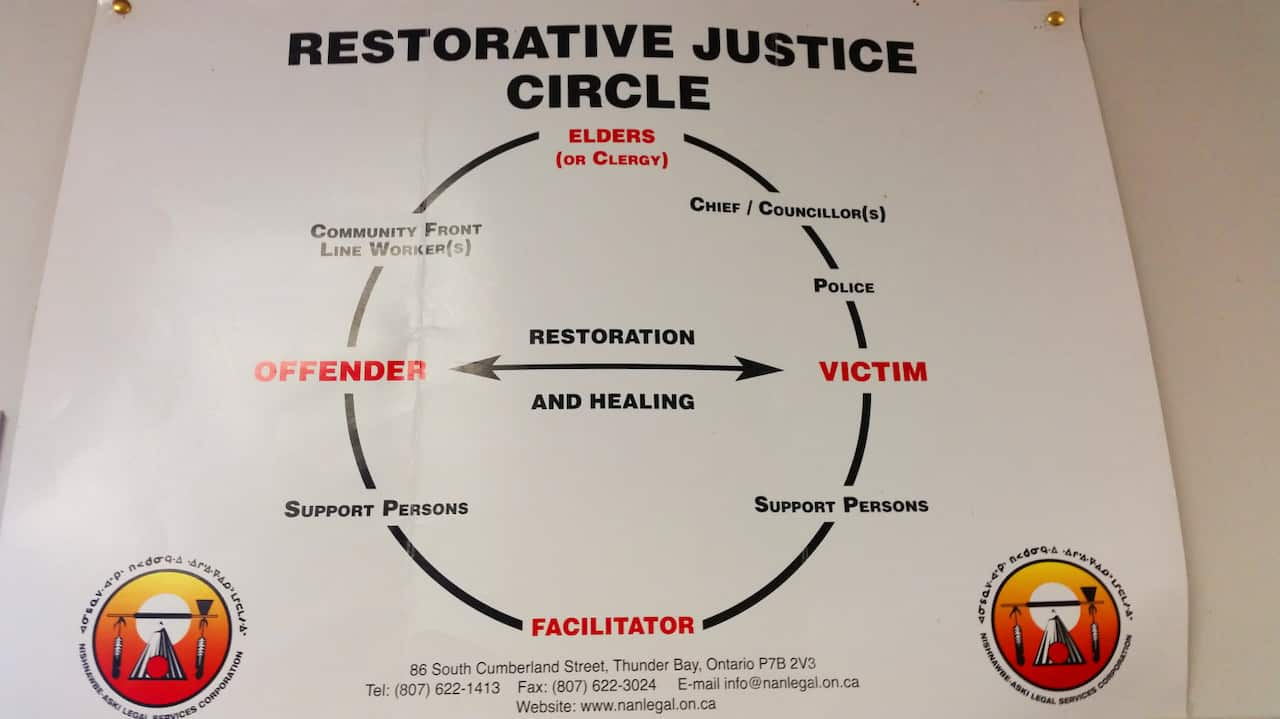

Nishnabwe Aski Legal Services (NALS) provide a restorative justice model for young people, based on traditional First Nations' mediation practices. Source: Ali MC

While a treatment plant was installed by the government to process water from the lake, plumbing was not directed from the plant to the houses. Instead, community members must fetch water from the treatment plant in buckets and barrels, and astoundingly, toilet facilities are simple outhouses that contain a long-drop in the backyard.

Instead, community members must fetch water from the treatment plant in buckets and barrels, and astoundingly, toilet facilities are simple outhouses that contain a long-drop in the backyard.

Many of the remote First Nations' communities have been influenced by Christian missionaries. Tensions still exists between religious and non-religious groups Source: Ali MC

I can only imagine what it must be like to sit in an outhouse in the middle of a deep winter when the weather is minus 40 degrees Celsius, and am shocked that such conditions exist in a developed country such as Canada, which is considered by many to be a bastion of human rights and political correctness.

A single diesel generator powers the entire electricity supply, yet I am told that it is often not enough power to run heating in the entire community, exacerbating the cold.

Instead, community members fetch wood from the forest to make fires for indoor heating.

Such conditions conspired in tragedy in April 2016, when nine members of the same family died in a house fire, including a baby, two young children and a community Elder.

This avoidable catastrophe occurred due the deadly combination of overcrowding, an open fireplace, and lack of access to running water to douse the fire once the wooden house caught ablaze.

Being such small community, the effects of the ongoing youth suicide epidemic is taking its toll.

It is a statistic little-known to most Canadians, let alone the rest of the world.

The Stolen Drums

Yet despair is not the whole story.

A new school has been built with first-class facilities, and a local police program has seen the young people build a boardwalk around the lake.

Ojibwe culture remains strong in Pikangikum, and there is a certain sense of community spirit and determination.

Within the newly built school, traditional 'woodland' style paintings adorn the walls, and Ojibwe language is still spoken by many in the community. At the community centre I met Lloyd Comber, an Ojibwe interpreter who works with the fly-in circuit courts.

At the community centre I met Lloyd Comber, an Ojibwe interpreter who works with the fly-in circuit courts.

Artwork on the walls of the new school. The Anishnabe 'Woodlands style' popularised by Norval Morrisseau celebrates the ecology that has ensured survival. Source: Ali MC

Lloyd is a long-haired Elder and former musician who has returned from Vancouver to Pikangikum to serve his people.

Lloyd was forcibly removed from his family in the 1960s and taken to an Indian Residential School, part of Canada's assimilation policy, and another Stolen Generation half a world away from Australia.

During his time at the residential school, Lloyd was regularly beaten and systemically raped - an experience not uncommon among First Nations' peoples throughout Canada.

Yet as well as the trauma, Lloyd also remembers a traditional sacred Ojibwe drum.

In a recent court testimony regarding the treatment of community members by police, Lloyd related a story of how his parents had held this drum in their trusted possession.

It was one of four community drums held in related nearby communities of Pikangikum, Poplar Hill, Little Grand Rapids and Pangaussi.

The drums embodied the spirit of the people who would come together on ceremonial occasions, and beat out age-old rhythms of healing and oneness.

These drums, Lloyd stated, were "the pounding, the heart. That's where everything centres... That gives them the feeling of belonging. That feeling, that sound of your mother's heartbeat, the earth's heartbeat."

But in 1969, the drum was stolen by a visiting white school principal.

Lloyd told the court that the theft of the drum marked the end of the old ways forever. Since then, none of Pikangium's children have heard the sound of those four drums in unison.

While the community of Pikangikum await some kind of action resulting from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's visit, perhaps it is only when the drums are returned, that Pikangikum's future will return as well.

An end to the old ways?

It is well documented that strong connections to culture is linked to better health, well-being and provides the foundation for resilient communities.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people might share a similar history with First Nations peoples of Canada, and face the same ongoing challenges, yet the strength and resilience of survival is also shared.

Lloyd's story of the stolen drum signified what he considered to be the end of the old ways.

Yet that the young people of Pikangikum are still strong in their language, cultural practice and art traditions means that there is a new beginning ahead.

Ali MC (Alister McKeich) is a writer, photographer and legal professional who holds a Masters in Human Rights Law. His work documents global human rights issues, and he has had the privilege of working with a number of Aboriginal communities here and internationally. He currently works at the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service. Follow @alimcphotos

Listen to our podcasts

Interviews and feature reports from NITV.

A mob-made podcast about all things Blak life.

Get the latest with our nitv podcasts on your favourite podcast apps.

Watch on NITV

The Point: Referendum Road Trip

Live weekly on Tuesday at 7.30pm

Join Narelda Jacobs and John Paul Janke to get unique Indigenous perspectives and cutting-edge analysis on the road to the referendum.

#ThePoint