Weak in health, but strong in heart :

Lucy Pepper’s motherhood bravery

Being an Aboriginal and raising seven young “half-caste” children during the Aboriginal Protection Act regime was harsh in itself, but done so whilst debilitated with illness made Lucy Pepper’s years as a mother, a story of survival.

By: Daniel James

Produced by: Sophie Verass and Daniel Gallahar

Tuberculosis is an insidious and debilitating condition with a long list of symptoms. Once rife throughout the world, it is now largely a third world condition.

In 1907, Lucy Pepper was a First Nation’s woman living in a first world country, relegated to existing in a third world conditions. Consumption or pulmonary tuberculosis, would be Lucy’s unwanted companion for much of her life. Her condition and the suffering that ensued would be made more arduous by the invisible hand of a bureaucracy that would leave its fingerprints over almost every aspect of her life.

Like her husband Percy, Lucy’s life, like the land itself, would be bound by a series of permissions and denials. Authorisation from men they would never meet and denial that would extend beyond life itself.

Lucy was born Lucy Thorpe on Lake Tyers Aborigines Station in 1884. The station was established in 1861 by the Church of England to house members of the Gunaikurnai nation, the survivors of the frontier wars that had decimated the local population. Two of the survivors were Lucy’s parents William and Lilian Thorpe.

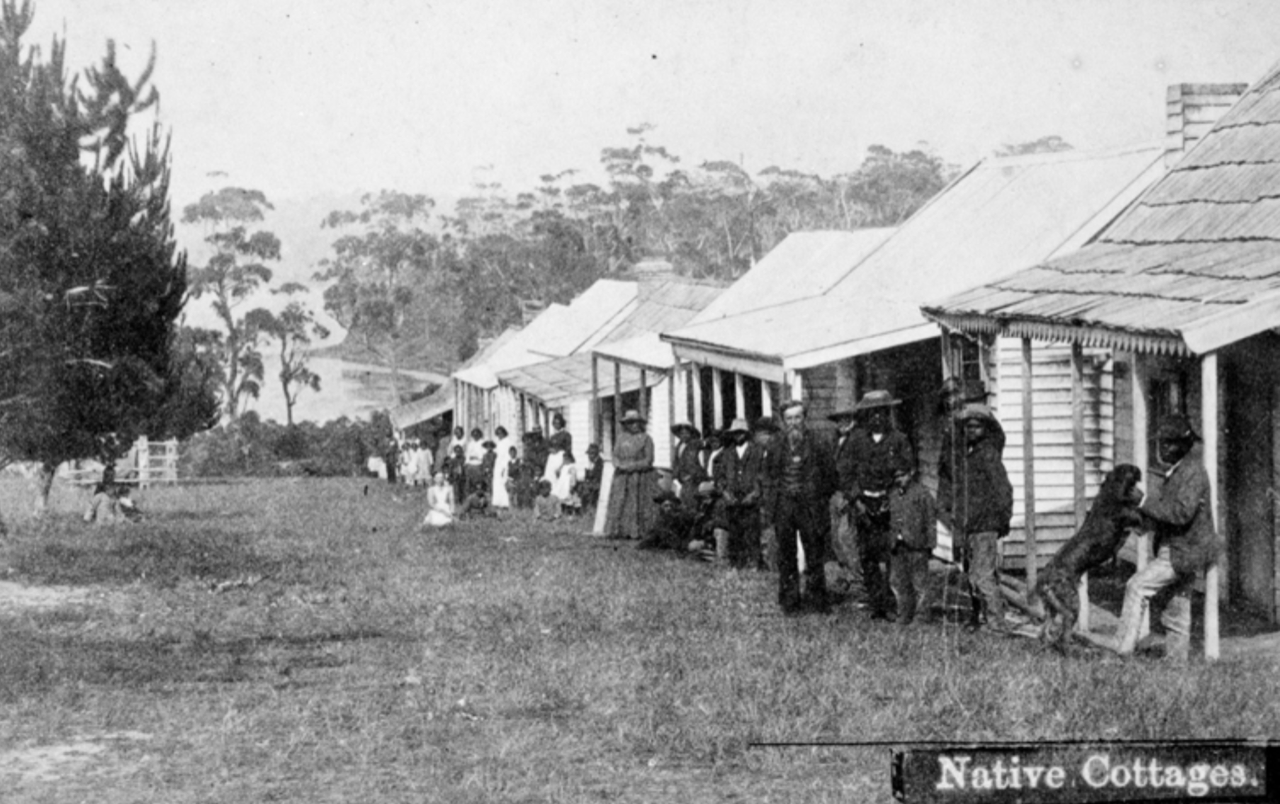

Lake Tyers Station in 1886, two years after Lucy’s birth.

Lake Tyers Station in 1886, two years after Lucy’s birth.

Gippsland, as it is now called, was the scene of some of the fiercest battles and darkest atrocities. Lucy was a single generation away from the immediate horror of those times, but the resulting trauma would linger for generation after generation after generation. Visit Lake Tyers today and you can feel the history through the beauty of the country and the stories it holds sacred to its people.

Lake Tyers was Lucy’s home; the land was hers, it was her ancestors’ home for millennia.

It was where the Church of England educated the survivors and their families in the way of God. How to find Jesus and how to lose their own cultural ways in the process. It was where Lucy learned to read and write, play piano to sing the hymns of the Lord.

The classroom could only extend so far. The missionary’s teachings did not reach the huts and the campfires where the oral teachings of her elders about the way life use to be.

For the time being, Lucy’s culture was to be whispered, the voice of ghosts passing down from generation to generation.

Forging out a living away from the station as a “half-caste Abo” is incomprehensible, but we do know it was during this time that Lucy met Percy, a Wotjobaluk man and fellow refugee. Designated by the Board for the Protection of Aborigines (BPA) as a “half-caste”, he like Lucy were not permitted to live off the stations they and their forbears had been shipped to as a supposedly final act of invasion.

The Aboriginal Protection Act, enacted in 1869 by the colony of Victoria (also known as the “half-castes” Act) gave extensive powers to the government's Board for the Protection of Aborigines over the lives of Aboriginal people, including regulation of residence, employment and marriage.

The Aborigines Protection Amending Act 1915 that followed, would provide the state with sweeping new powers to remove children from their families without a hearing and authorise total control over the lives of “half-castes”.

The Peppers had become cultural refugees on their own land, just as the BPA had dutifully planned and carried out their role of ‘protection’. There would be no going back home for the Peppers. They were the displaced.

The transient nature of their existence, as Percy pursued work, is evidenced by the birthplaces of the couple’s seven children, all birthed across the vast expanse of Gippsland. They went wherever Percy could get work, they would seek asylum wherever that work led them.

Lucy Dora was born in Sale in 1903, William Phillip, born in Cunninghame in 1905, as was Louisa Gwendoline (Gwen), in 1907. Alice Ethel was born in 1908, Stratford, Sarah Lillian in Orbost, 1910, Samuel Joseph, Sale 1911 and Lena Mary, Stratford 1915.

All seven children were born by the time a stable income was best sort by a life in the infantry. Work was easier to come by on the western front that it was in the townships of regional Victoria. And so in 1916, Percy was shipped off to face the horrors of war and the promise of glory and more importantly a land settlement upon his return.

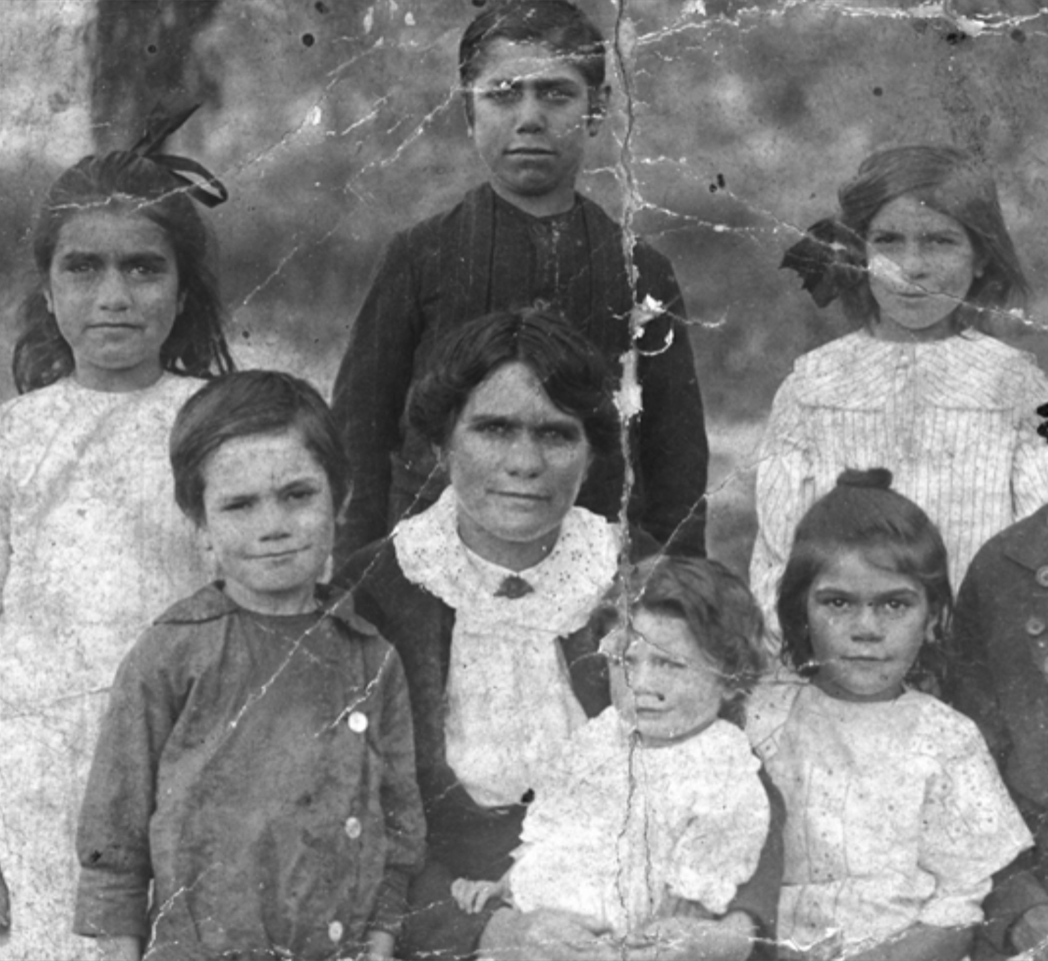

Studio portrait of the Pepper family, circa 1912 - (LEFT TO RIGHT) BACK: Dora and Percy with Sam; FRONT: Gwendoline, Alice, Sarah, Lucy and Phillip. Lucy and Percy's youngest daughter, Lena, was born in 1915.

Studio portrait of the Pepper family, circa 1912 - (LEFT TO RIGHT) BACK: Dora and Percy with Sam; FRONT: Gwendoline, Alice, Sarah, Lucy and Phillip. Lucy and Percy's youngest daughter, Lena, was born in 1915.

Lucy was alone with the seven children; Percy was ten thousand miles away.

120 miles away faceless men in Melbourne through the ink of a pen continue to erode the culture of Aboriginal people.

As an example, correspondence between Bruce Ferguson, the manager of Lake Tyers station and the BPA. Ferguson wrote to the BPA upon request of clarification of the level of Aboriginality of Lucy’s sister Alice Connolly upon her request to stay on the station to look after their ailing mother Lilian.

FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: Lucy Pepper, her youngest daughter Lena, niece Alice and daughter Gwendoline, early 1920s

FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: Lucy Pepper, her youngest daughter Lena, niece Alice and daughter Gwendoline, early 1920s

The correspondence is clinical, it is cold, it is calculated, it is racist. It is an instrument of cultural genocide. And it was typical.

Ferguson’s letter to the Board of July 1922 read:

“Sir,

I have to report with reference to:-

(1) Colour of Mrs J Connolly :- Mrs Connolly, her husband and child, age about 3 yrs, are almost white in appearance. They call themselves half-caste, but there is no family so nearly white as they are residing on the Aboriginal station.

(2) Whether I think provision should be made for them on the Aboriginal station. In view of the Boards instructions that no one – nearer white than half-caste is to receive assistance, the visits of this family to the station have not been encouraged. They usually appear after dark and seek permission to remain until morning, but it very rarely happens that they leave next day. If they were half castes I would recommend that provision should be made for them here, but being so nearly white they should be able to do better off the station...

Yours faithfully,

BRUCE FERGUSON mgr”

All in accordance with the Act, the Act that would govern Lucy, Percy and their children for over half a century.

It was now the 20th Century and it was the invaders final push to wipe out Aboriginal people by continuing to mow down access to their traditional way of life, to sever any threadbare semblance to culture and ultimately, to each other. The act and its various amendments would remain the law of the land until 1969; a point to remember next time you sit down with an elder.

If they were born and lived in Victoria, chances are they were born under the menacing shroud of the Aborigines Protection Amending Act 1915.

The Act meant that no Aboriginal person in the state of Victoria was beyond the reach of the Board, least of all Lucy, Percy and their children. Perhaps Lucy’s greatest achievement during the war years —during all her years— was to keep the children together despite incapacitating illness and being under the glare of suspicious eyes of would-be do-gooders that would happily relieve her of her children in the name of Christ.

She also managed to keep them in touch with culture by sending some of the older children to spend time with their grandparents William and Lilian.

We have an insight into Lucy’s ongoing health problems when she wrote to the Chief Secretary of the Victorian Government in February 1915 requesting to leave Gippsland for warmer areas on account of her condition.

She wrote:

“Dear Sir,

I am writing to you for a little help as I want to leave Gipps-land before winter sits in I have been suffering for the last 7 years with tubical of the left lung and also bleeding lungs and in winter I am subject to hemmerages, and the Dr says a change would do me good I would like to go over to the Western District Purnim at Easter once I get over to Purnim I can get a little help with my children I have six and the eldest is only eleven and they cannot do for themselves when I am sick and my husband has to knock of work to look after me and over at Purnim I have relations that would help me a lot my husband is working on the railway line to Orbost but that wont last long and he cannot leave me by myself. I am camped out with him as for himself he suffers at times and cannot get full time.

Time it is only hand to mouth and we have a very hard struggle to get a living I am compelled to write to ask you if you could give me and family a pass at Easter to go to Purnim both my husband and myself are half caste Aboriginals my Husband to get work on the railway line over there the police in Cunninghame can let you know what a hard struggle we have with sickness as I never know when I take bad and I dread to stay in Gippsland for the winter the Dr ordered me away to another climate in winter hoping you will help me and give us a pass trusting to hear from you shortly as I would like to go away at Easter there is always [sic] a drawback if my children are not sick I am and oblige.

Your humble servant

LUCY PEPPER”

Percy, wounded himself, would return home from France in 1918 after being granted a discharge to care for an ailing Lucy. They would live in a soldier settlement at Koo We Rup, faraway from Lake Tyers, a long way from home. It is where she would spend her last days.

On her last day, during her last moments, her daughter Gwendoline , then 16 years of age, sat at the family piano and played the old hymn for her mother, Jesus Loves Me, This I Know:

Jesus, take this heart of mine;

Make it pure and wholly Thine.

Thou hast bled and died for me;

I will live henceforth for Thee.

Yes, I love you Jesus

Lucy, her family and the people of Lake Tyers all requested that she be buried on the station so she could be buried with parents William and Lilian. Survivors to the last.

Their request was denied and Lucy remains buried at Packenham cemetery a long way from home. There’s no doubt Lucy loved Jesus. There’s no doubt that as the light faded, Lucy was surrounded by love. She had the love of her husband, the love of her family but she did not have the love of her country.

A country in which she would forever be denied.

Daniel James is a Melbourne-based writer of the Yorta Yorta Nation. Lucy Pepper is Daniel’s great great grandmother. Follow Daniel @mrdtjames