Listen to Australian and world news, and follow trending topics with SBS News Podcasts.

TRANSCRIPT:

"Gaza is a hundred per cent nothing like I've ever witnessed in all the humanitarian deployments that I've done."

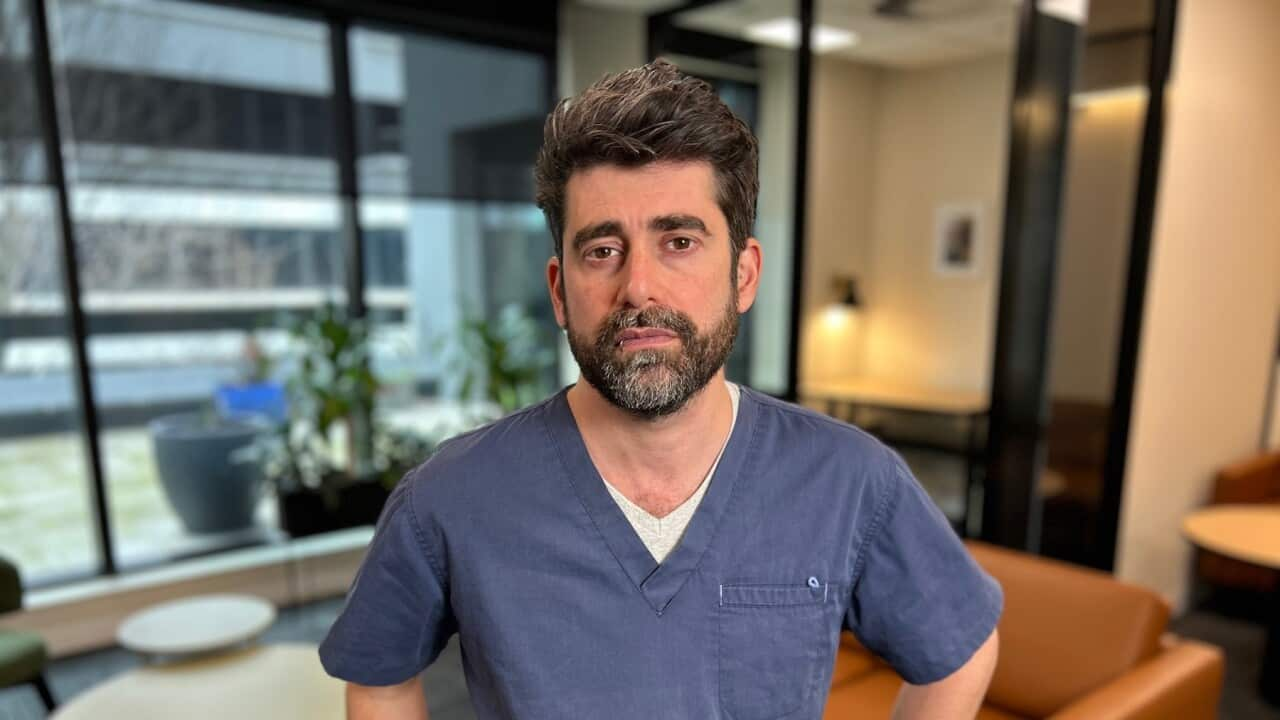

As a veteran of war zones, Melbourne emergency nurse Jean-Philippe Miller has seen more than most but he says conditions at Gaza’s Rafah field hospital are next level.

"We're in the middle of a conflict, you're hearing active hostilities, you're hearing gunfire, you are hearing blasts, you are hearing drones 24/7."

Mr Miller has just flown back to Gaza, in one of the deadliest years for aid workers. So far, Red Cross and Red Crescent have lost 18 staff and volunteers.

Despite the risks, Mr Miller is on leave from a Melbourne hospital to serve on Gaza’s medical frontline.

"Sometimes I wonder why am I going back? And I think, when you are here, you are very much an observer. I'm seeing on the news the suffering that people are enduring over there. But as a humanitarian, you have an opportunity to flip that dynamic. And when I go into this location, I'm no longer an observer. I'm an active participant, and yeah, I can help save a life. I can help alleviate suffering."

It’s not just civilians in Gaza who are suffering.

The Red Cross delegate says after 22 months of conflict, hospital workers are exhausted and hungry, too.

"We've got 350 ICRC staff members on the ground and they're also struggling to access food and clean water on a daily basis. The only meal that the hospital is able to offer our patients is a small portion of rice because that's all that's available."

Since early 2024, Mr Miller has deployed to Gaza three times with the Australian Red Cross ... but fears this month will be his toughest yet.

"From a hospital perspective, we are seeing increased numbers of patients attend with signs of malnourishment. And that's extremely concerning because we know that adequate nutritional intake is paramount in order to aid recovery."

Daily critical care work in Australia has prepared him for most medical emergencies.

But in Rafah’s over-crowded field hospital, it’s the faces of injured children that haunt him most.

"Looking after the paediatric patients is definitely incredibly challenging, it is distressing. I find it horrific to see these injuries that these children have endured."

Fewer than half of Gaza’s hospitals are functioning, according to the United Nations, and among those that are, Mr Miller says supplies are low.

"The healthcare system in Gaza has been decimated. It's essentially in ruins. In the field hospital, we are very limited. We don't have all our basic supplies. These aren't like luxury items, these are the bare bones that you require in an emergency department and in a ward. Things like gloves, sutures, things like gauze and bandages. These are the things that we're running out of."

Despite Israeli assurances it abides by International Humanitarian law, or IHL, Mr Miller says medical teams are at risk.

"It's confronting. We are very much told when we go into Gaza that our safety can't be guaranteed. Obviously, ICRC take security very seriously and they do everything to mitigate risk."

Safety of staff is paramount for Adrian Prouse, the Acting Executive Director of International, Australian Red Cross.

"There is no way to eliminate the risk when you're sending someone into a situation like Gaza. And that for me is probably where real heartache kind of sets in, in terms of how I feel about putting people like JP and our local staff in terms of the conditions that they operate under."]]

International humanitarian law is a set of rules which seek to limit the effects of armed conflict.

Yet aid workers face grave dangers in many global conflicts, according to Dr Eyal Mehroz, Senior Lecturer in Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Sydney.

"Gaza is an extreme case, not the only one. There's Sudan and other places. The Geneva conventions have been left aside on many, many occasions during the last 22 months. And I think this is really something that the international community has been insufficiently strong on trying to prevent."

Mr Miller is now back in Gaza, with the support of his family and girlfriend, and determined to help those most vulnerable.

"I've had friends tell me not to go. I don't think of myself as brave necessarily. Yeah. I think about the immense needs. I want to show solidarity for our colleagues. It's really important for them to see familiar faces and to know that we haven't forgotten them. I think there's genuine fear from them that the world has forgotten them ... "