Listen to Australian and world news and follow trending topics with SBS News Podcasts.

TRANSCRIPT

Seafood sales are soaring in the lead up to Australia Day, especially at Sydney’s new fish market.

But do we always get what we pay for?

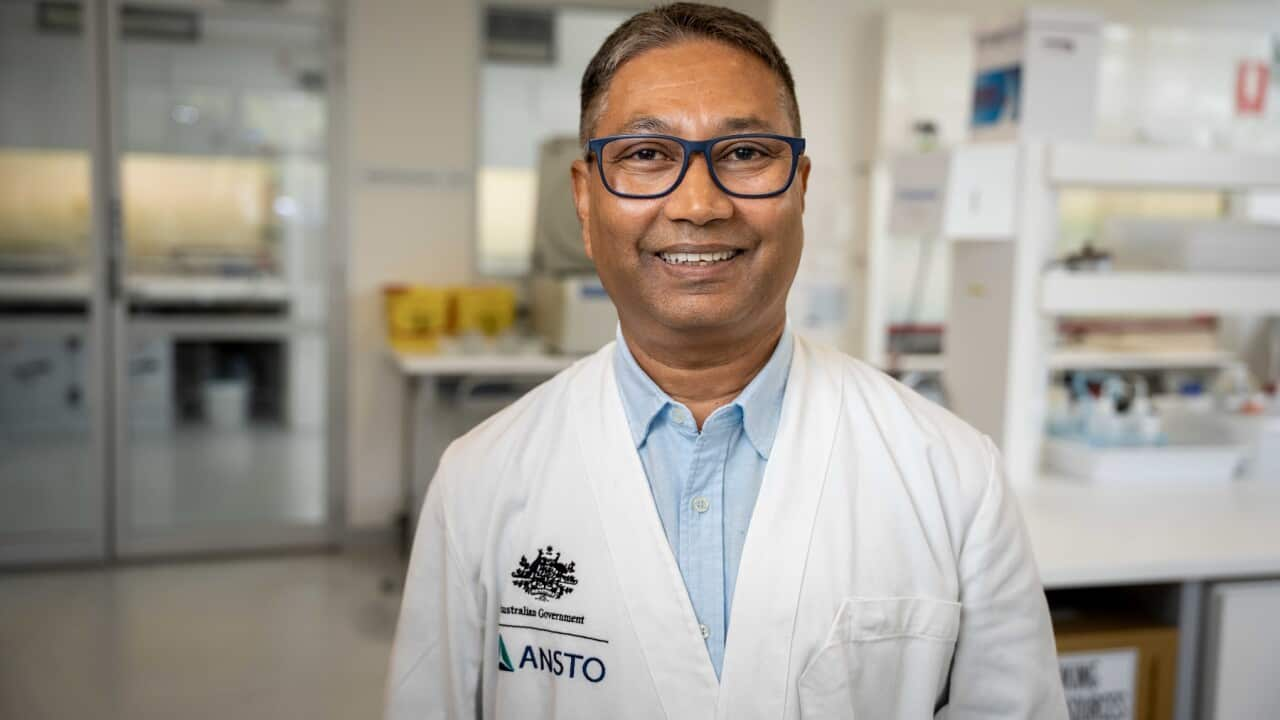

To build trust with consumers, the market is working with a group of nuclear scientists to determine fish origins. Dr Debashish Mazumder leads the food provenance research project at the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO)

“This technology we developed particularly analyses the environmental fingerprint of a food. We decode these environmental fingerprints through machine learning algorithm which can, with a high degree of accuracy, confirm its source of origins of this product. “

By tracing elements like calcium or copper inside fish tissue, the fingerprint shows exactly where a fish bred, fed and grew. In the lab, a handheld scanner adapted from mining also helps to determine whether a fish labelled Australian wild-caught was, in fact, farmed in Asia. That’s called ‘food fraud’.

“It’s basically, tricking customer about the source and the quality by making money. So, this technology ensures the label is correct. Our fisheries management is regarded as one of the best fisheries management in the world. So, that is why we have a great reputation in the world, particularly that Australia produce a high quality premium product.”

Australia’s seafood industry is valued at up to $4 billion annually.

Australia exports a lot of seafood but of all that is sold here, around 60 per cent is imported.

And that multiplies the fraud risk, with estimates around 10 per cent is mislabelled.

Karen Constable is principal consultant at Food Fraud Advisors.

“The act of purposely selling fake, mislabelled or substituted food for economic gain is food fraud and it is a global multibillion dollar problem. We have increasingly complex supply chains and ways of buying and selling big bulk commodities. So globally, the industry actually thinks that food fraud is getting bigger and worse. “

Worldwide food fraud is estimated to cost up to 75 billion dollars annually, around $3 billion in Australia alone, according to a 2021 AgriFutures Australia report.

High-risk sectors include wine, honey and seafood.

Professor Jes Sammut leads the aquaculture research group at the University of New South Wales.

He says industry supports new technology designed to verify food origins, including seafood.

“Seafood has a very long supply chain from where it's produced right through to the retail sector. And all along that supply chain there are different participants who may be involved in fraudulent activities. So, it's critically important that we have technology that can verify where something has come from, but also importantly how it was produced, whether it was wild caught or whether it was farmed. “

The food fraud health risks are also huge.

Globally, the World Health Organisation says contaminated food causes 600 million illnesses and 420,000 deaths each year.

Dr Mazumder says contamination is a serious problem in Australia, too with more than five million cases of food poisoning reported each year, some of which are fatal.

“It could be because of the bacteria. It could be because of the virus and because of the metals like, mercury, lead and other things. So basically it compromises the health condition.”

From July this year, Australian hospitality outlets will be required under new laws to label the country of origin on all seafood dishes, or face fines! Ms Constable welcomes the move.

“As Australians, if we think we are buying Australian seafood, we really want to know that we are getting what we paid for, and there is a risk that cheaper seafood from overseas can be substituted for Australian-grown seafood.”

Ms Constable says fraud can also occur when products sold offshore for premium prices are mis-labelled as Australian-grown.

“You might have foods like cherries or lamb or prawns that are claimed to be Australian, but that really aren't. It's very hard to prosecute against those food fraudsters without some technology to back you up.”

According to Dr Mazumder, Australia’s native Kakadu plum is among the products most vulnerable to substitution.

“We purchased from nine different suppliers and all the suppliers from overseas. And we found all of them are fake and not a genuine Kakadu plum powder.”

The ANSTO team is taking its technology worldwide, collaborating with scientists to build vast data bases as part of a new food provenance project. Science Program Leader Patricia Gadd explains.

“We create a database of all these food products from all over Australia. And not only Australia now, a lot of Southeast Asian countries are actually together with us. So we are building a database with a robust number of samples and, different types of food products as well.”

racing food provenance has been a decade long passion project for Dr Mazumder who hopes the new technology will soon make food origins more visible for all.

“One day the consumer might go and use their smartphone to scan the small barcode and they can see all the elemental compositions, which is related to a particular the environment and confirm the product they are buying coming from an authentic source.”